By Dr. Trần Quang Minh

Kentucky Colonel Medal

Nguyên Tổng Giám Đốc Tổng Nha Nông Nghiệp

Nguyên Thứ Trưởng Bộ Nông Nghiệp

Nguyên Thứ Trưởng Bộ Thương Mại và Công Kỹ Nghệ Kiêm Tổng Cục Trưởng Tổng Cục Thực Phẩm QUốc Gia

Epilogue

My service was abruptly interrupted in 1969 when I was drafted in the general mobilization following the Tet Offensive and sent to a special boot camp at Quang Trung Training Center with a lot of high officials in the government including young ministers of draft age. Since every official high and low was affected by the general mobilization decree, it was understood that, at the end of the nine weeks of basic training, the government entity, where one worked, had to write the MoD to request a transfer back home. Mr. Nguyen Duc Cuong, the future MTI Minister and Dr. Nguyen Thanh Hai, the future NAI Rector who were in my Nguyen Hue Battalion were sent home on time. I worked for two ministries—the MoA and the MoEd—doing very important civilian jobs, but neither one made the request to the MoD to get me out of the military. So while everybody went home upon completion of boot camp training, I was still kept there with the group who would be sent to the Thu Duc Reserved Officer Training School, since I had a college education, to be trained for officer duty in the armed forces. Years ago I learned that if your place of work did not like you, it would not request your transfer back either from boot camp or from officer training school. I figured that if nobody wanted me to carry on my important civilian duty then I will choose a military career because I dearly loved my country and I truly believed in our anti-communist cause. In fact, I always thought that I would made a good military leader because of my fearlessness and aggressivity. But, my wife thought otherwise: when she did not see me back as planned, she worried and called her friend who was Mr. Hoang Duc Nha’s wife. Nha at that time was President Thieu’s Special Assistant must have called someone because the next day I was honorably discharged from the Army to go back to my civilian job.

In a way military service was good for me because it taught me discipline, resiliency, hard work, gumption, and teamwork. These were things I found very valuable in the discharge of my official duties and at the origin of my successes as a leader of men tackling difficult jobs.

Nguyên Tổng Giám Đốc Tổng Nha Nông Nghiệp

Nguyên Thứ Trưởng Bộ Nông Nghiệp

Nguyên Thứ Trưởng Bộ Thương Mại và Công Kỹ Nghệ Kiêm Tổng Cục Trưởng Tổng Cục Thực Phẩm QUốc Gia

Epilogue

My service was abruptly interrupted in 1969 when I was drafted in the general mobilization following the Tet Offensive and sent to a special boot camp at Quang Trung Training Center with a lot of high officials in the government including young ministers of draft age. Since every official high and low was affected by the general mobilization decree, it was understood that, at the end of the nine weeks of basic training, the government entity, where one worked, had to write the MoD to request a transfer back home. Mr. Nguyen Duc Cuong, the future MTI Minister and Dr. Nguyen Thanh Hai, the future NAI Rector who were in my Nguyen Hue Battalion were sent home on time. I worked for two ministries—the MoA and the MoEd—doing very important civilian jobs, but neither one made the request to the MoD to get me out of the military. So while everybody went home upon completion of boot camp training, I was still kept there with the group who would be sent to the Thu Duc Reserved Officer Training School, since I had a college education, to be trained for officer duty in the armed forces. Years ago I learned that if your place of work did not like you, it would not request your transfer back either from boot camp or from officer training school. I figured that if nobody wanted me to carry on my important civilian duty then I will choose a military career because I dearly loved my country and I truly believed in our anti-communist cause. In fact, I always thought that I would made a good military leader because of my fearlessness and aggressivity. But, my wife thought otherwise: when she did not see me back as planned, she worried and called her friend who was Mr. Hoang Duc Nha’s wife. Nha at that time was President Thieu’s Special Assistant must have called someone because the next day I was honorably discharged from the Army to go back to my civilian job.

In a way military service was good for me because it taught me discipline, resiliency, hard work, gumption, and teamwork. These were things I found very valuable in the discharge of my official duties and at the origin of my successes as a leader of men tackling difficult jobs.

Part 1 of 4

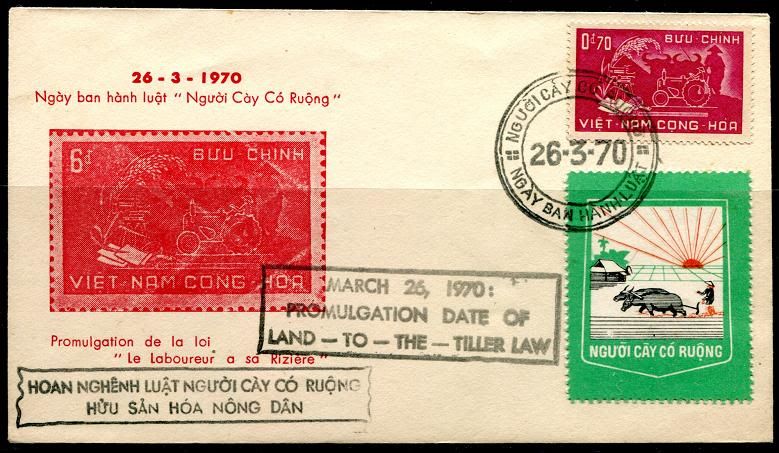

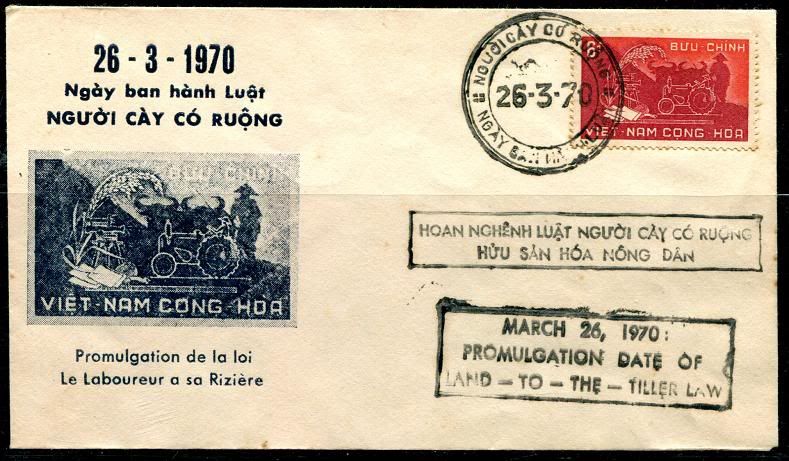

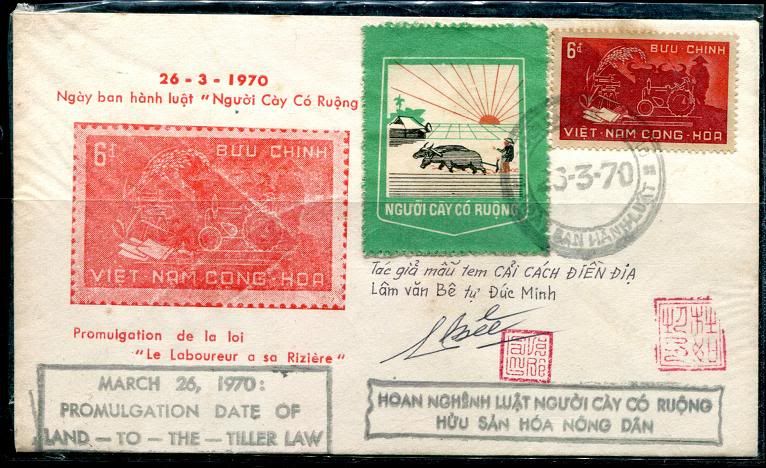

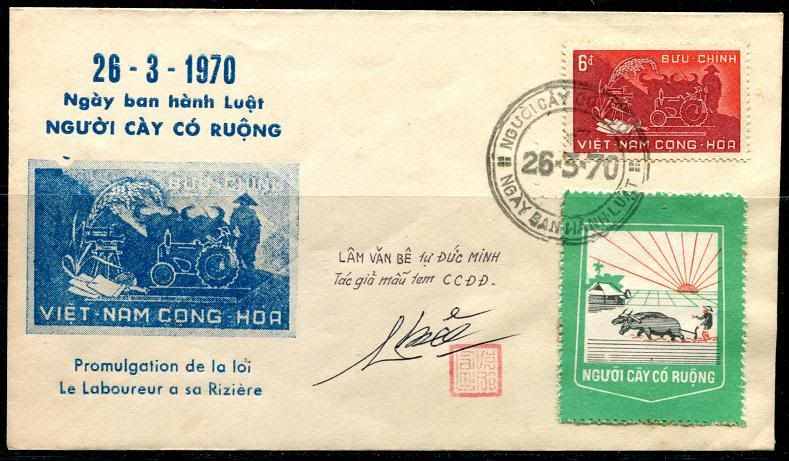

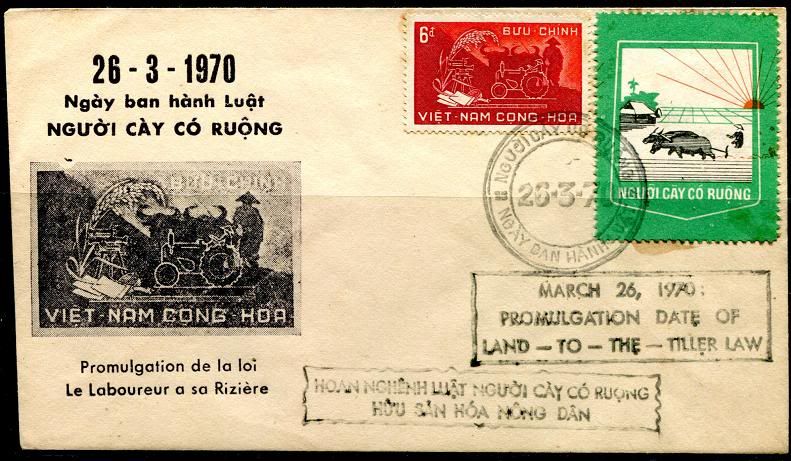

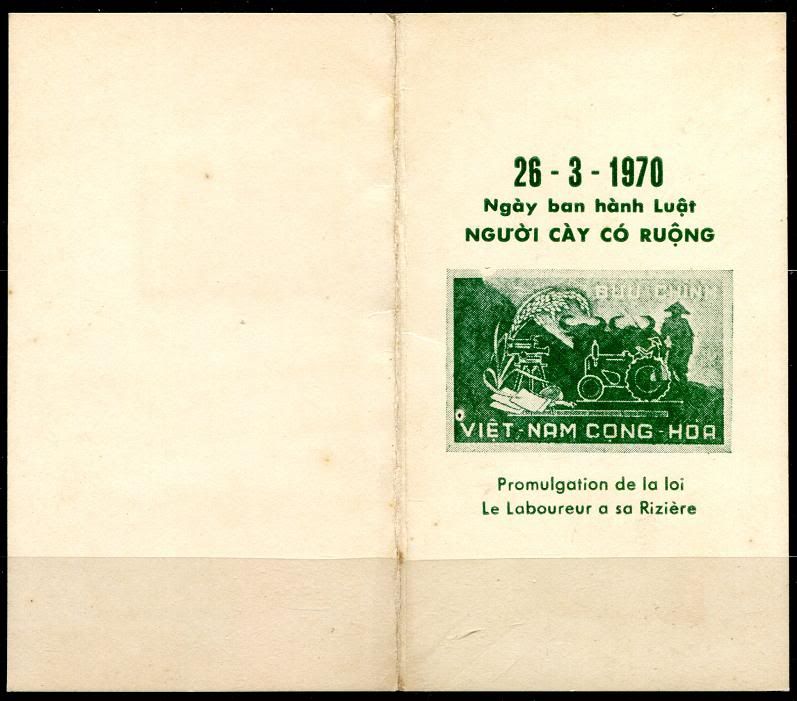

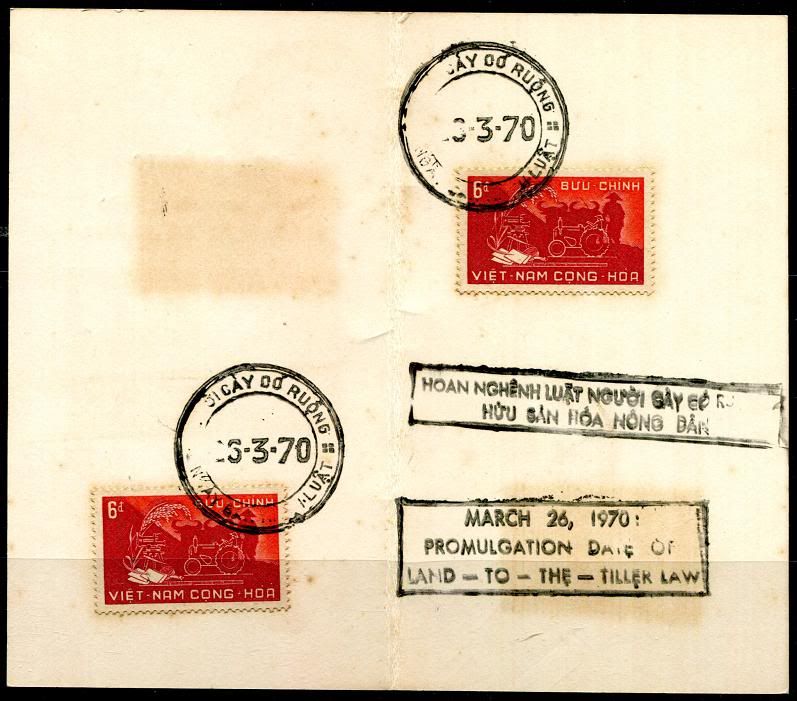

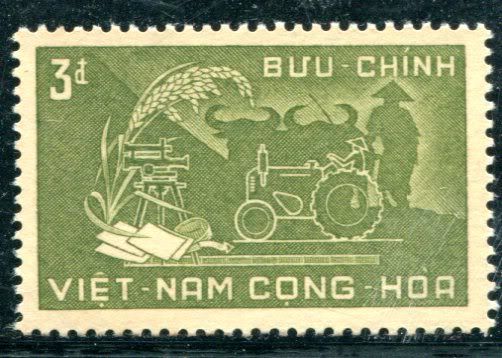

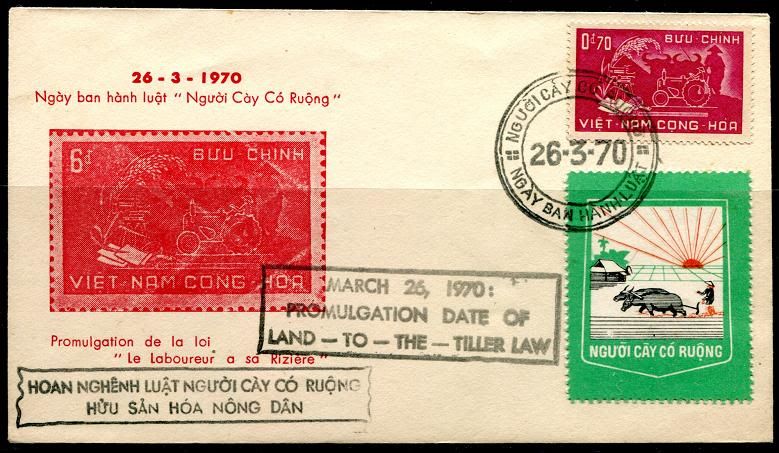

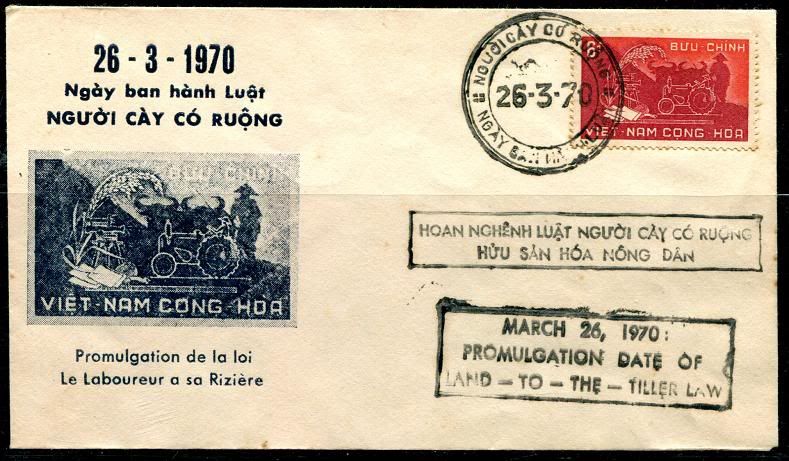

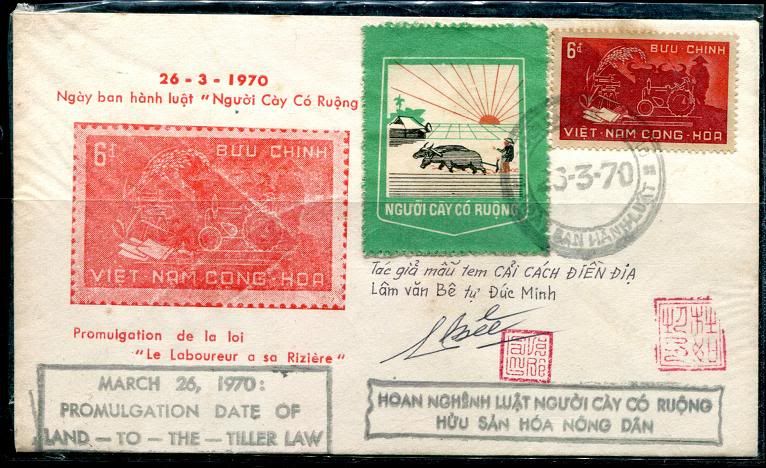

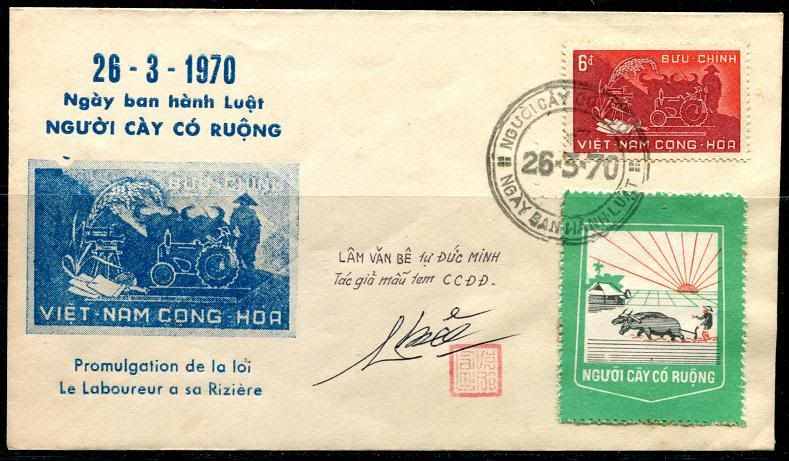

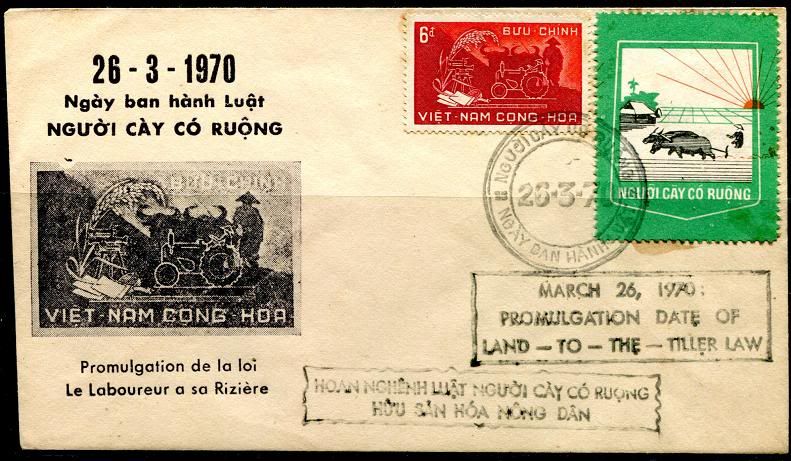

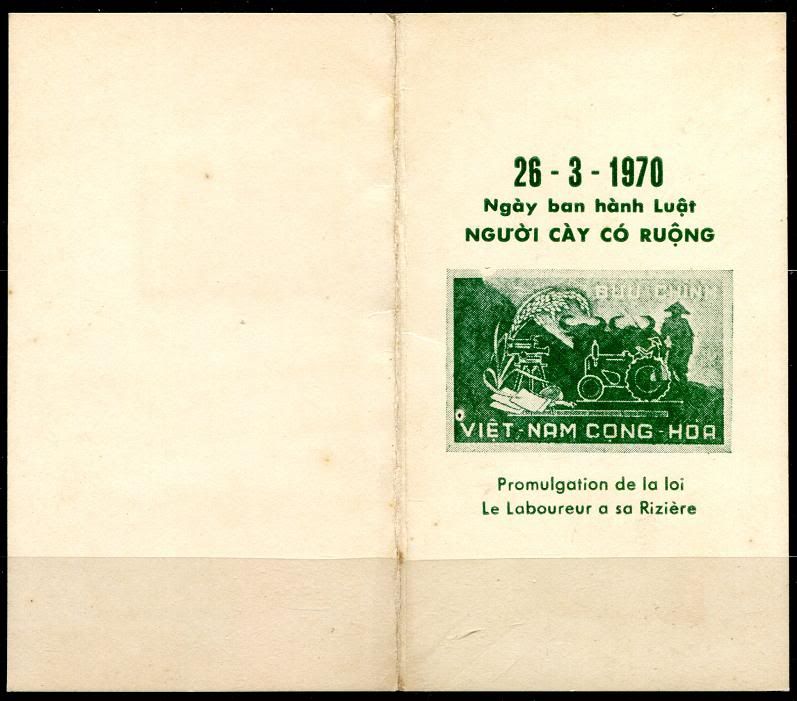

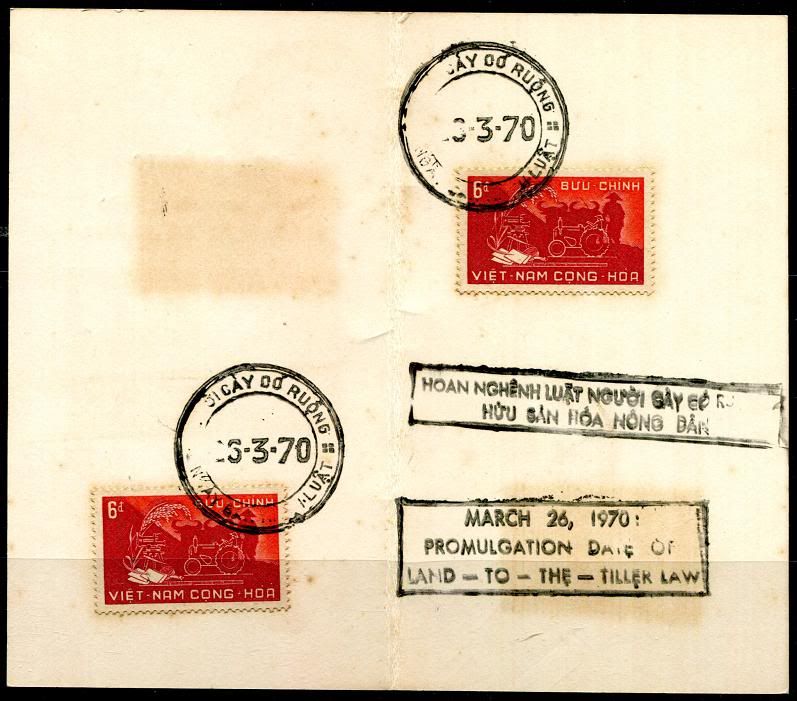

BUILDING AN OWNERSHIP SOCIETY FOR A RURAL SOCIAL REVOLUTION

THE ‘LAND TO THE TILLER PROGRAM’

Chữ viết tắt:

RVN : Republic of VietNam (Viet Nam Cong Hoa)

MoD: Ministry of Defense (BỘ Quốc Phòng)

MoEd: Ministry of Education: Bộ Quốc Gia Giáo Dục

NAI: National Agriculture Institute: Trung Tâm Quốc Gia Nông Nghiệp (tức turong2 Cao Đẳng (hoạc ĐH) Nông Nghiệp SG, đường CƯờng Để)

Director of Cabinet: Đổng lý văn phòng Bộ

MR: Military Region (Quân Đoàn/Quân Khu/Vùng chiến thuật) chẳng hạn MR IV : Quân Đoàn 4

SSAFAS: Superior School of Agronomy Forestry and Animal Science , same as NAI, tức trường Đại Học Nông Nghiệp trước khi đổi tên thành NAI

VLDC: Village Land Distribution Committee Hội đồng duyệt xét cấp đất ở địa phương

VAC: local Village Administrative Committee Hội Đồng Xã

MoEd: Ministry of Education: Bộ Quốc Gia Giáo Dục

NAI: National Agriculture Institute: Trung Tâm Quốc Gia Nông Nghiệp (tức turong2 Cao Đẳng (hoạc ĐH) Nông Nghiệp SG, đường CƯờng Để)

Director of Cabinet: Đổng lý văn phòng Bộ

MR: Military Region (Quân Đoàn/Quân Khu/Vùng chiến thuật) chẳng hạn MR IV : Quân Đoàn 4

SSAFAS: Superior School of Agronomy Forestry and Animal Science , same as NAI, tức trường Đại Học Nông Nghiệp trước khi đổi tên thành NAI

VLDC: Village Land Distribution Committee Hội đồng duyệt xét cấp đất ở địa phương

VAC: local Village Administrative Committee Hội Đồng Xã

PLAS: Provincial Land Affair Service: Ty Điền Địa (Tỉnh)

DGLA: Directorate General of Land Affairs : Tổng Nha Cải Cách Diền Địa (trục thuộc Bộ Nông Nghiệp)

CLRC: Central Land Reform Council Hội đồng cố vấn Cải Cách Điền Địa

DGA: Directorate General of Agriculture Tổng Nha Nông Nghiệp (trực thuộc Bộ Nông Nghiệp)

MTI: Ministry of Trade and Industry Bộ Phát triển Thương mại và công kỹ Nghệ (tức là Bộ Kinh Tế)

MLRAD: Ministry of Land Reform ans Agriculture Development: Bo Cai Cach Dien Dia va Phat Trien Nong Nghiep - goi tat la Bo Nong Nghiep

NFA: National Food Administration: Tổng Cuộc Thực Phẩm Quốc Gia, co quan tự trị (giống như Ngân Hàng VIệt Nam Thương Tín) có CHủ Tịch Hội Đồng Quản Trị (Chair of board of director) là TỔng Trưởng Kinh Tế (lúc đó là TT Nguyễn Đúc Cường, 35 hay 36 tuổi) và điều hảnh bởi 1 Tổng Cuộc Trưởng, chúc vụ này ngang hàng với Thứ Trưởng Bộ Kinh Tế (lúc đó là TỔng Minh, nhận chúc vị sau khi rời chúc vụ Tổng GD NN và làm Thứ Truong Bộ NN)

DGLA: Directorate General of Land Affairs : Tổng Nha Cải Cách Diền Địa (trục thuộc Bộ Nông Nghiệp)

CLRC: Central Land Reform Council Hội đồng cố vấn Cải Cách Điền Địa

DGA: Directorate General of Agriculture Tổng Nha Nông Nghiệp (trực thuộc Bộ Nông Nghiệp)

MTI: Ministry of Trade and Industry Bộ Phát triển Thương mại và công kỹ Nghệ (tức là Bộ Kinh Tế)

MLRAD: Ministry of Land Reform ans Agriculture Development: Bo Cai Cach Dien Dia va Phat Trien Nong Nghiep - goi tat la Bo Nong Nghiep

NFA: National Food Administration: Tổng Cuộc Thực Phẩm Quốc Gia, co quan tự trị (giống như Ngân Hàng VIệt Nam Thương Tín) có CHủ Tịch Hội Đồng Quản Trị (Chair of board of director) là TỔng Trưởng Kinh Tế (lúc đó là TT Nguyễn Đúc Cường, 35 hay 36 tuổi) và điều hảnh bởi 1 Tổng Cuộc Trưởng, chúc vụ này ngang hàng với Thứ Trưởng Bộ Kinh Tế (lúc đó là TỔng Minh, nhận chúc vị sau khi rời chúc vụ Tổng GD NN và làm Thứ Truong Bộ NN)

IRRI: International Reseach of Rice Institute, cha đẻ các giống lúa thần Nông than ngắn, lá thẳng mà bắt đấu là IR8

Shortly after I got back from boot camp after nine weeks of basic military training, I resumed my previous work, which was teaching at the Superior School of Agronomy Forestry and Animal Science (SSAFAS). Even though I had other faculty members substituting for me to teach my three courses during my absence, they were just doing stop-gap jobs. I had to a do a crash make-up session involving extra time at night and during week-end that my poor students had to endure. Students really had to like, respect, and admire me to put up with all these hardships. There was no shortage of harassment that my poor students had to endure. And over the years, when I enlisted them in all my programs I amply returned all their kindness and gave them all due consideration and recognition.

The Accelerated Protein Production Program (APPP) was still on the fast tract of progress during my absence thanks to my able second in command at the Tan Son Nhut Livestock Experiment Station (TSNLES): Mrs. Nguyen Thi Quoi. I taught her how to get along and work with my American counterpart and advisers and she did just that and more. Women seemed to be able to work with Americans a lot better than men in my experience, but, unfortunately there were not too many women in position of authority in our society. I was lucky that the 3 chiefs of sections under me were all very able female technocrats.

The nice thing about working with the private sector in programs such as the APPP was that the participants joined the effort for their own benefit and profit unlike working with public servants who viewed everything as an eight-to-six job. I had a few American retired private sector experts in the livestock industry that USAID contracted to help our private sector entrepreneurs. They worked wonders with our people to the point that when one particularly good poultry expert had to go home after his contract expired, my father came to see me to ask if I could intervene with USAID to extend his contract because the people in his poultry association wanted the American around longer to pick his brain. I said, “Dad, I could not do that. I could not possibly tell the Americans how to run their doggone business. It’s not done before.” He protested, “What do you mean you could not do that? You ran the APPP for two years. You must carry some weight with USAID.” I just sheepishly answered, “You asked me to do something nobody has ever done before. I am not comfortable doing that.”

So, he asked my Uncle Huynh Van Lau who was the Chairman of our Lower House Agriculture Committee to join him and both of them went to see the Director of USAID/Saigon to request an extension of the poultry expert’s contract. I didn’t know how they did that because neither of them spoke English. But you know what? They got USAID to extend the contract. I ran into JB Davis who was the Associate Director of USAID for Agriculture and our Minister’s counterpart shortly afterwards. He told me, “Dr. Minh, do you know that in all the years I have been working for USAID all over the world in the past thirty five years, your father and your uncle were the only ones who would and could tell USAID how to run its business. They said you would not want to tell us how to run our doggone business. Good for them!” All I could do was to murmur a weak, “I’ll be damned!”

In retrospect, I think that these American and South Viet Namese private sector entrepreneurs were instrumental in getting our livestock industry burn all these long intermediate steps between start-up and take-off and blossom. The poultry and swine livestock industry reached commercial level in a few short years—three to four years at most. After that the government role was minimal. Once that was taking root, the Directorate of Livestock Production and Protection’s main job was to assist the small farmers, the people who raised fewer than a 100 broilers or layers and a couple of pigs in their backyard to supplement their fixed income. We had a lot of those.

I remember growing up my mother every year grew a pig in the beginning of the year inside our house, believe me or not. At the end of the year she sold it to a meat market and had enough money to get all her seven kids new clothes, new shoes, and pocket money (li xi) for the Tet (Lunar New Year) celebration. Most other South Viet Namese did that. The pig ate kitchen refuge from cooking preparation and left-over from meals. My mom even taught the pig how to use our Turkish toilet.

The last pig she raised was so smart that she did not have the heart to sell it and by that time my dad was pretty wealthy from his poultry business that my mom did not need her live “piggy bank” any more. That pig grew up to be like a 300-lb monster and we kids used to ride her all over the neighborhood. I even made my pocket money by charging neighbor kids one piaster per ride around the block. The pig was so scared of my dad that when she heard his car she would dash from the front door to the kitchen to seek my mom’s protection, knocking people, mopeds, bikes, chairs, and tables along the way, oinking oinking oinking loudly from beginning to the end. I related this story to emphasize the beneficial unintended consequence of the APPP: the creation of a livestock cottage industry among fixed income urban people besides the livestock industry. This activity really softened the inflationary pressure on them and their families and contributed to the wildly successful APPP in suburban setting.

This must have caused some repercussion at the highest level of our ministry because, one day in 1969, Mr. Nguyen-Thanh-Qui, the Assistant Minister to the newly appointed energetic thirty-five-year-old Minister of Land Reform and Agriculture Development (MLFAD), Cao Van Than, whom President Thieu appointed to carry out his social revolution, more specifically the Land To The Tiller land reform program, called me to his office to convey the Minister’s intention by telling me, “The Minister wishes to form a dynamic team to help him implement the Land To The Tiller land reform program. He wants you to be his Director of Cabinet (similar to Chief of Staff in this country). So are you interested?” To that I said, “I want to thank the Minister for his consideration. I will accept his offer if he allows me to continue my teaching job at the SSAFAS as the previous Minister did because I don’t want to lose my root. I was on loan here from the Ministry of Education. I teach only two hours of surgery a week now because we have two American-trained PhD faculty members just join us who will teach my other two courses.”

Minister Than obviously knew what he was doing because he bypassed at least four levels of bureaucracy to promote me from the eighth position to the third position in the ministry hierarchy, something rarely if not ever done in our country. That certainly did not sit well with nor endear him to the hierarchy of the ministry, to say the least. My Mom must be right because this promotion was pivotal in my career rise. It was a high and solid stepping stone.

I always consider the shaping up of the agricultural technocrats of South Viet Nam as extremely important for the building of our rural society. I always view the college years as crucial time in the development of young people because many of the attitudes and ideas they form while in college would be the compasses that guide them for the rest of their lives. After seeing that the clueless college students wrought havoc in the US foreign policy I did not want South Viet Nam to have similar problems in the middle of its life-and-death struggle to remain free. We sorely needed a lot of good dedicated smart technocrats to build our agriculture-based economy as President Park Chung Hee admonished. We were lucky to have a dozen classes of these young but devoted agriculturists who performed not only superbly, but sometime above and beyond the call of duty.

Minister Cao Van Than had no problem with my request. And so, at twenty nine I was the youngest Dong Ly Van Phong (Directeur de Cabinet = Director of the Cabinet) of a major ministry South Viet Nam ever had. It was getting to be a routine from this time onwards: I was invariably the youngest official to ever hold each and every position of leadership of great importance in the hierarchy of our government spanning three ministries, happy circumstances that bolstered my mother’s contention that I was born under very good stars. This position was a French creation similar to but not quite the same as the job of Chief of Staff in the American officialdom. The position ranks third in power right below the Minister and the Vice-Minister (if there exists one) or the Assistant Minister (if there is one). In our government set up, the Vice Minister post is a cabinet rank appointed by the President whereas the Assistant Minister is not and is named by the Minister himself to assist him in his heavy duty.

The job of the Director of Cabinet, which is a staff function and not a line function is mainly to:

1. Handle the Minister’s political and public relation dealings that he himself does not want to do for any reason;

2. Represent the ministry in negotiating with foreign countries concerning foreign aids at the ministry level;

3. Represent the ministry in inter-ministerial work at that level;

4. Attend all the regional meetings with the General Commander in Chief of different MR’s when the Minister could not go;

5. Carry out any special mission that the Minister assigns;

6. Give the Minister his personal opinion on matter of importance concerning the Ministry’s operations and management to help him make his decision.

In that position, as examples, I was called upon to:

1. Handle all these members of our General Assembly or their representatives or city and province councilmen or trade associations or farmers organizations who came to us for favors, complaints, grievances on their constituents’ or members’ behalf or on their own behest;

2. Negotiate assistance from South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, the Philippines for our agricultural development programs. That was why I travelled overseas quite a lot and attended banquets all the time on the Minister’s behalf. I also participated in many yearly international meetings like FAO, SEATO/SEAMES, etc. as a representative of our country or of my ministry;

3. Participate in all the coordination and cooperation meetings of the ministries concerned for resolving certain problems that required high inter-ministerial authorities: monthly HES pacification meeting, refugee resettlements, foreign exchange allocation, military deferment, etc.;

4. Go to the regional meetings with the MR Commander and his Province Chiefs to unravel problems stemming from the implementation of a myriad of programs of our ministry at the grassroots level.

The MLRAD had more programs going on everywhere than any other ministry because sixty five % of our people lived off agricultural activities and every month I had to go to these long meetings, most of the time in MR IV where most of our programs were concentrated. Sometimes, even President Thieu or the Prime Minister himself went down to Can Tho with the ministers concerned and met with the people in charge of important programs like the land reform and pacification programs. In time of war, there was nothing like the full power of the presidency to light fire under the butt of military authorities at regional and local levels to get them to assist in the implementation of civilian programs. I liked to give to our Minister especially difficult problems beyond our control that I detected during my many inspections in the boonies for him to give to the President to raise at these meetings. It showed the local authorities that the highest level of government was aware of local bottlenecks and hang-ups. President Thieu always said that he would visit the locality again to see how the problem was resolved; it would be solved in a hurry;

5. Spend a lot of time in the provinces on routine inspection of program implementation. The MLRAD had more provincial services than any other ministry. South Viet Nam had forty four provinces up and down the country, sixteen of them were in MRIV where 11,000,000 South Viet Namese lived at the time, 6,000,000 of those were farmers. The MLRAD had two Directorates General (Tong Nha), the Directorate General of Land Affairs (DGLA) that implemented the land reform program and the Directorate General of Agriculture (DGA) that carried out at any time some two dozens of major agricultural development programs in the government’s Five-Year Agricultural Development Plan and many smaller projects in the nine sectors of agriculture. The DGLA had its thirty five Provincial Land Affairs Service (PLAS = Ty Dien Dia) in most provinces and none in highland provinces where there was not any rice-land to justify the cost of setting up a service there. On the other hand, the DGA had nine Directorates covering nine sectors of agriculture and most of them had provincial services or regional offices, which created an extensive and complex local organization in the far-flung provinces.

In anticipation of the coming passage of the Land To The Tiller Law being heatedly debated in our General Assembly, Minister Cao Van Than was spending almost half a year ramping up the massive organization and the intensive training that would be needed to carry out that revolutionary program. I said massive and intensive because eventually it would involve some 50,000 central and local, intra- and inter-ministerial people, mostly in the far-flung 2,100 villages, i.e., more people involved in any single government civilian program in the history of our country. USAID-Saigon in the beginning had only one land reform expert. Eventually to keep up with us it had 35 of them in its land reform division alone, in all likelihood the biggest group of all.

I was lucky to be involved at a close up position in the planning and execution of the biggest and most complex government program our country ever undertook and to see its eventual successful completion in record time by a 35-year-old, dynamic, and effective minister who cumulated two massive portfolios at the same time: the Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Rural Reconstruction. No wonder, he was trained at the university best known for development administration: Pittsburgh University School of Administration and International Relation. This experience was of extreme value for me in my next two big responsibilities I was called upon to discharge. There was nothing more importance than on-the-job training for leadership of big program planning and implementation.

With that preliminary introduction let me next talk about the most important and most meaningful achievement of the Second Republic of Viet Nam bar none: land reform. At the outset, I want to state that this was no ordinary land distribution, but truly it was a rural social revolution. Unlike most revolutions, ours was a very peaceful and equitable one as you will find out later. Under the leadership of President Nguyen Van Thieu, we launched this rural social revolution by building almost overnight an ownership society. I was lucky to have an once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to participate in the implementation of that historical undertaking. So, allow me the privilege to share with you that unique experience which was so close to my heart.

Basically, I will be sharing with you how the government of the Second Republic of Viet Nam was building an ownership society under the gunpoint of an implacable enemy who was bent on derailing it at every turn. It was not just any kind of ownership society, but an ownership society of the free-private-entrepreneurial type. And this undertaking was not for the enjoyment of any privileged class of our citizenry that exerted great influence or wielded strong power, but for the benefit of the underprivileged and long-suffering mass of our people. President Thieu wanted to create, in other words, almost overnight a rural middle class, made up of the majority of our people.

To realize that rural revolution, the Second Republic of Viet Nam launched several programs on direct orders from President Thieu—a massive land reform program and an ambitious Five-Year Agricultural Development Plan. I said massive because it was the biggest land redistribution program in Viet Nam and, for that matter, in Asia. And I said ambitious because it was the agricultural development program that brought about food self-sufficiency to a war-torn economy in record time. I will concentrate here on the most important program which was also the most successful of that endeavor—the Land-To-The-Tiller Program (LTTTP).

BUILDING AN OWNERSHIP SOCIETY FOR A RURAL SOCIAL REVOLUTION (II)

Background

First, it is worthwhile to go over some background information on land tenure throughout the ages in South Viet Nam to understand the rationale behind this vast undertaking. Land tenure management in Viet Nam went through many changes since time immemorial. Here are some important ones.

Dynastic Land Reforms:

Throughout most of our 2000 years of history the Viet Namese people had lived under different royal and imperial dynasties. During these feudal times, under the self- proclaimed mandate from heaven, emperors and kings literally owned all the country’s lands, which they doled out to mandarins, generals, and veterans as rewards for their past meritorious service and their unwavering allegiance to the empires or kingdoms. These rulers also accorded lands to newly created villages as source of their revenues to run their local government—these lands were known as communal lands (cong dien).

There was one noticeable land development scheme that resulted in the reclamation of large marginal swamp lands performed by Nguyen Cong Tru, a famous mandarin of the Nguyen Dynasty under Emperor Tu Duc. This project opened up new lands for the resettlement of a lot of landless people and for the creation of new villages. But we did not have too many of these undertakings in ancient times. The adventurous people themselves had to band themselves up and blaze trails in their southward migration to build new lives and new fortunes for themselves, most of the time at heavy cost of lives and limbs, in the last six centuries, much like the American pioneers in their westward movement.

All through successive dynasties, little ever changed except for minor tinkering in the creation of feudal societies where the lot of the peasants did not improve much through the ages.

Land Management under the French Domination:

Then, beginning in the 1860’s and in the early Twentieth Century under the French domination, the French colonialists allowed their citizens and the Viet Namese who served them in their administration, and thus deserved to acquire French citizenship, to exploit virgin lands for cultivation of both industrial plants (hemp, jute, sugar cane, tea, coffee, and rubber trees) and rice or secondary crops (beans, peanut). The colonial administration also used public funds to finance vast land reclamation schemes and private citizens who disposed of means could buy these lands at auctions upon completion of the project. Of course, these auctions were out of the reach of common poor people.

Consequently, newly cleared lands were usually bought exclusively by the rich, famous, influential, and powerful people in our society. South Viet Nam had roughly 15,000,000 acres (6,000,000 ha) of cultivable lands. Half of that total or 7,500,000 acres (3,000,000 ha) was under cultivation and was owned by some 50,000 landowners of all sizes. Some 6,000 largest landowners possessed nearly 3,000,000 acres (1,200,000 ha) or 40% of the cultivated land. In the Mekong Delta alone, 430 French citizens owned 625,000 acres (250,000 ha) or more 8% of the total land under cultivation.

I need to open some big parentheses here to give the readers some insight as to why land reform was not successful during the First Republic and the Interregnum Period. I knew three of these French citizens mentioned above very well. They were brothers and were my great uncles Gaston Do Van Diem (Great Uncle Eighth) and Charles Do Van Kia Great Uncle Tenth), two former District Chiefs of many provinces in the Mekong Delta during the colonial time and the middle brother Do Van Son, my mom’s father, was also a former District Chief like his siblings. [Actually my Mom was born out of wedlock when her landlord father had an illicit affair with a beautiful daughter of one of his tenant farmers because his legal wife was sterile]. These three brothers rose to the top administrative rank of Doc Phu Su Dac Hang (Doc Phu Su Exceptional Class) in the late 30’s and early 40’s and were awarded the prestigious French Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honor) the highest civilian medal for their forty years of meritorious services for the colonial authorities. I was told that they were honored for having cleared hundreds of thousands of acres of rice land and dug hundreds of kilometers of canals and built thousands of kilometers of rural roads in their many Mekong Delta districts over these four decades of colonial service to be thus recognized. Naturally they themselves also owned thousands of acres of rice land each here and there in the Delta wherever they used to hold office. The Do’s clan was very big. It came from a Do ancestor who was a notable in the French colonial village administration in Chau Doc. He was the Chief of the Council of Notables (Hoi Dong Xa) of a village. He had nine children.

At the time my Mom sent me to Saigon for my high schooling I stayed the first six years in a house on 14 Nguyen Thanh Y Street in Dakao District of Saigon with Great Uncle Gaston Diem, the titular head of the clan because he was the oldest surviving son of the bunch. That clan had numerous descendants who were village administrators of various capacities throughout the Mekong Delta, especially in Chau Doc, An Giang, Dinh Tuong, Long An, Bac Lieu Provinces. It even had men who fought in France’s army against Hitler. It also sent a member to Paris as deputy from Cochinchina in the French General Assembly. Quite a few people in the clan married French men and women. It counted no less than three colonels [one, Colonel Hoang Van Ty who married my seventh aunt, was General Thieu’s second in command at the Dalat Military Academy] in the Republic of Viet Nam Army and Air Force assimilated from the French Armed Forces. It also had numerous lesser ranking officers in the RVNAF except Uncle Quang, the tenth son of my Great Uncle Do Van Diem. Nobody knew what got into him, but he joined the Viet Minh to fight the French. Of course, the communists did not trust people of his class, so he was only a medic in their forces. He came home quite disillusioned after Dien Bien Phu.

Every year the clan’s members gathered for ancestors’ worshipping a couple times at my great uncle’s house true to our Viet Namese tradition. All I heard vehemently discussed there by at least a couple hundred relatives was how to use all the loopholes there were in the land reform laws to keep the land in each descendant family. Uncle Four Nguyen Van Trinh, the Director General of Land Affairs (DGLA) and his son-in-law Dang who was the Provincial Land Affairs Service (PLAS) Chief in Go Cong Province held court in telling everybody what to do to fight expropriation, circumvent the regulations, and evade the laws or request for expropriation and compensation for land abandoned in remote areas or taken over by the VC’s. They were mostly absentee landlords at that time, living in France or in Saigon.

The powerful Do Clan was dead set against land reform because they thought it was unfair, illegal, and smacked of communist highhandedness and class warfare. When the French gave South Viet Nam independence after the Dien Bien Phu debacle they bought back all the rice lands owned by the French citizens to give to the government of Viet Nam, under Emperor Bao Dai as Chief of State with Ngo Dinh Diem as Prime Minister, supposedly to be distributed to landless farmers.

But somehow all my distant uncles and their descendants still had rice lands from the clan’s big holdings. I remember when my parents moved to Saigon in the late 50s they bought a unit of my great uncle Do Van Kia’s new three-story sixty-unit condo that he got from the French at the foot of the Hien Vuong Bridge in exchange for giving up a part of his land holdings. From my great uncle Do Van Diem came three interesting individuals who played some important roles in our regime’s history: 1) His son-in-law, Le Tan Nam who married his oldest daughter, held a few ministerial portfolios (mostly Ministry of Justice = Bo Tu Phap) early in Nguyen Van Tam’s, Tran Van Huu’s, and Ngo Dinh Diem’s administrations. He was the first Viet Namese to receive the French Licence-en-Droit (JD) and was Tan An District Chief and Saigon Mayor for many years; 2) Le Tan Nam’s son—Le Tan Loc was the perpetual Director General of Viet Nam Thuong Tin (Viet Nam Credit Bank), the big government bank; 3) Another son-in-law who married his third daughter, my uncle Nguyen Van Trinh, the DGLA who was in charge of implementing the Diem’s and the Interregnum Period’s agrarian reform programs. Obviously, it was a poor choice to pick a member of a big land-holding family who didn’t believe in agrarian reform to do land redistribution. Besides, a mandarin like President Diem would not be someone who would have a burning desire to redress social justice through meaningful, drastic, and revolutionary land reform. So, not much enthusiastic work had been done for more than a decade of land reform schemes, not to mention a lot of evasions of the law perpetrated by landowners through insider information.

That was why when Minister Cao Van Than was entrusted by President Thieu to implement his landmark Land To The Tiller Land Reform Program, a new landless young Northerner Director General of Land Affairs named Bui Huu Tien was put in charge of the DGLA and a brand new team of young and dynamic technocrats was put in place to carry out vigorously the hard and pressing work.

That did not mean that the Do Clan was not patriotic: it had two officers posthumously awarded the highest medal of valor of SVN, the Bao Quoc Quan Chuong, akin to the American Medal of Honor. My DGLA Chief uncle Nguyen Van Trinh’s oldest son who was my cousin and fellow J.J. Rousseau high school mate, Lt. J.G. Jean Nguyen Van Tri was the South Viet Namese second in command of one of our Navy ships that was sunk by the stronger Chinese communist naval forces during the naval engagement for the defense of the Paracels Islands on order from President Thieu.

He was mortally wounded by enemy’s rocket fire, rescued by his fellow combatants on a raft that was drifting in the South China Sea for almost a week before they were rescued by a foreign merchant ship. When his blood was attracting sharks that endangered his men and knowing that he would not survive, Tri ordered his men to toss him overboard to end his suffering. They refused to obey his order. They eventually had to do that after he died to get rid of the trailing sharks. Tri was one of the two South Viet Namese naval officers who were honored as national heroes by both our regime and the current communist regime for being killed in combat fighting the Chicoms. The other officer was another one of our ship commanders who was killed in the same battle. This was the famous battle discussed at the Cornell Symposium by Rear Admiral Nguyen Van Ky Thoai, Commander of that fateful MR I Naval Forces.

I relate this family story just to give you an insight on one of the reasons why President Diem’s land reform failed and to give a probable explanation as why only in Long An, An Giang, and Chau Doc Provinces, where most of the people of that clan exerted strong influence in the local government, almost half of all the grievances stemming from the Land To The Tiller Program (LTTTP) implementation originated. You can multiply this situation by at least 300 since there were that many similar clans in South Viet Nam to understand the magnitude of the obstacles President Thieu and Minister Than must have overcome to carry the Second Republic’s social revolution to satisfactory completion.

The French colonial administration unintentionally aggravated the land tenure problems by vastly increasing land holdings in the hands of a few powerful people, usually French citizens or Viet Namese having French citizenship by serving in their colonial administration or the village notables who governed the colony at the grassroots level. The French colonialists in power at the time did indeed open up vast areas of lands in their colony in the South through forest land clearings for industrial plantations and through swamp land reclamations in the Mekong Delta for rice farming. But these efforts did not benefit many landless farmers because the local authorities at different levels managed to amass through collusion, deception, ruse, trick, fraud the bulk of these lands for themselves.

Agrarian Reform Under the First Republic of Viet Nam:

Real agrarian reform was first approached under the First Republic of Viet Nam from 1955 to 1963. But that weak first attempt was an unworkable program following the promulgation of Ordinance 57 in October 1956, that achieved poor results. During these eight years, little was accomplished as expected, for one reason or another. A few plausible reasons were discussed above.

Before the events of Ordinance 57, there were two attempts by President Ngo Dinh Diem to control the excesses of the land tenancy system in South Viet Nam by controlling rents and by giving a greater degree of land tenure to tenant farmers. Ordinance 2, promulgated on January 28, 1955, mandated that land rent be between 15-25% of the average harvest and be formalized with a three-year written contract to reduce evictions. Ordinance 7, promulgated on February 5, 1955, was designed to protect the rights of tenants on new and abandoned lands to encourage cultivation (squatters’ rights protection). These ordinances also reduced rent payments after crop failure and gave renters first right of refusal should the owners decide to sell their holdings.

Now let’s take a closer look at land reform under the First Republic of Viet Nam, the first weak attempt at real reform of land tenure. Unfortunately this was not done the right way! Otherwise, we probably would not have to fight the Viet Nam War as Roy Prosterman and Chester Bowles said. That lost decade between 1954 to 1964 and the following Interregnum Period between 1964 to 1967 could have been used effectively to launch a rural social revolution similar to the one President Nguyen Van Thieu implemented sixteen years later complete with a vigorous agriculture-based economic development program. The ensuing transformation of the South Viet Namese society would be such that it could have very well pre-emptd any NVN’ s attempt to subvert SVN free government and its stronger economy. It was a terrible missed opportunity that led to horrific consequences for tens of millions of South Vietnamese!

In a nutshell, the legal basis of the First Republic of Viet Nam land reform program was covered by Ordinance 57 signed by President Ngo Dinh Diem in October of 1957. It put a 250-acre (100 ha) limit on rice land ownership and gave the landlords the right to keep another 37.5 acres (fifteen ha) for ancestral worship. Any excess land would be expropriated and owners would be compensated. Expropriated land would then be sold to farmers in installments. Landowners received ten per cent of land price in cash and ninety per cent in government bonds redeemable in twelve years. The huge 250-acre cap left only 1,130,000 acres (452,000 ha), which made up only twenty % of SVN domestically owned lands, available for expropriation from some 2,035 landlords. These lands were usually not prime rice lands because the landowners claimed the best lands as their 250 acres (100 ha) retained property for themselves or their relatives or their 37.50 acres (fifteen ha) of ancestral worship land: These expropriated lands were usually not the best rice lands near rivers, canals, and rural roads, but were abandoned lands in remote areas or cultivated lands in communist-controlled areas from which landlords could not collect rent anyway or lands far away from transportation networks. On the other hand, the prime land that each landowner was allowed to keep—287.5 acres—would continue to keep up to eighty tenant farmers in perpetual bondage because the average rented plot of land was 3.5 acres (1.4 ha) in the Delta.

At that time, the government also disposed of two other chunks of public domain lands that it did a pretty poor job of redistribution to needy and deserving tilling farmers: 1) 662,000 acres (265,000 ha) “squatter claimed” lands; 2) 375,000 acres (150,000 ha) of “land development center” agricultural lands.

The program had so many loopholes that were easily exploited by devious landlords and sharp lawyers to avoid expropriation. Prosterman and Riedinger gave an excellent study of these problems in their “Land Reform and Democratic Development” book for anyone interested in a deeper understanding of this program.

As Roy Prostetrman et al reported, “…The cumulative result of all the program as of the end of 1967 was the distribution of some 275,000 hectares (687,000 acres) of land to 130,000 families. This represented less than 1/8 of SVN cultivated land, with benefits going to barely 1/10 of those who had been wholly or substantially dependent on farming land as tenants.”

Now, just what exactly was accomplished during those seven years under the Diem Administration?

Because of the adoption of complex and centralized bureaucratic procedures for the distribution processes, from 1957 to 1963, only fifty per cent of expropriated lands were redistributed or roughly 560,000 acres (226,000 ha). Understandably, poor farmers had little money to buy necessities of life much less to buy lands. So, only roughly 100,000 out of approximately 1,000,000 existing tenant farmers (almost all in the Mekong Delta) benefitted from the program. (The 900,000 difference will be discussed below). The 625,000 acres (250,000 ha) of French citizens’ lands was barely touched because only fewer than 12,500 acres (5,000 ha) were distributed to 2,900 families, mainly in Ninh Thuan and Binh Thuan Provinces. The difference between the results achieved at the end of 1967 and 1963 was the result in land distribution achieved during the Interregnum Period: 687,000 – 560,000 = 127,000 acres (275,000 – 226,000 = 49,000 ha) given to 130,000 – 100,000 = 30,000 families. This period was a period of chaotic government due to military coup after military coup and a time of increasing insurgency war fomented and perpetrated by the communist North Vietnamese.

So the political, social, and economic impact of this land reform was minimal and inconsequential. That was why the insurgency war intensified during this time. The battle for the hearts and minds of the South Vietnamese people could not be won. And President Diem tried other ineffective and costly schemes like agro-villes to change the countryside to no avail.

Shortly after he became Chief of State, President Thieu realized that to prosecute the war against the communists effectively he had to focus on land reform a lot more than the previous administration. On September 1968, he began to formulate and enunciate his own concept of land reform by giving an accurate assessment of the situation: The government of the RVN was faced with a long standing problem of social injustice which demanded solution if the pacification was to be effective. The practice of tenant farming, which in effect, made the tenant farmer slave to the land and to a continuous cycle of poverty, had to be abolished. This was a monumental historical decision of epic proportion by a leader of Viet Nam.

President Thieu hoped to achieve three main goals with the transformational land reform program he contemplated:

1. Provide social justice for the long suffering Viet Namese peasants

2. Undercut the Viet Cong land distribution scheme to gain the political support needed to establish government control of the countryside

3. Provide the basis for a sound agricultural economy

That brings me to a detailed discussion of land reform under the Second Republic of Viet Nam that I had first-hand knowledge with when I was the Director of Cabinet—the third highest-ranking official of the ministry--of Minister Cao Van Than, the new dynamic, hard-working, driven, and knowledgeable Minister of Land Reform and Agriculture Development, a close Adviser of President Thieu in agrarian reform and economic development, the architect, and the implementer of the most successful land reform program of all time in recent history. It was the kind of land reform program that the New York Times unabashedly called ”probably the most ambitious and progressive non-Communist land reform of the twentieth century.” From a leftist newspaper, this was an unadulterated compliment.

Land Tenure in South Viet Nam:

Before going into the details of President Thieu’s land reform program, it is a good idea to cover the state of land tenure prevalent at the time when President Thieu proclaimed the Second Republic of Viet Nam in 1967.

At that time, some 60% of the South Viet Namese population of roughly 17,000,000 were peasants or a little more than 10,000,000. They were mainly rice farmers. And three fifths (3/5) of these farmers or roughly 6,000,000 lived in the Mekong Delta where 80% of rice was produced. The remaining two fifths (2/5) of the farmers or roughly 4,000,000 lived in the narrow coastal plains of the Central Lowlands.

According to available statistics from UN/FAO, in the early 1960s there were 1,175,000 farming households, but only 257,000 (or 22%) farming families owned all their lands in mainly the Mekong Delta. Their average acreage was roughly four acres (1.7 hectares). Another 334,000 families (or 28%) farmed an average of six acres (2.4 ha) of rice land both rented and owned: with 2/3 of total area rented from landlords and 1/3 of the area owned. There were 521,000 farming families (or 44%) who farmed an average of 3.5 acres (1.4 ha) of lands that was totally rented from landlords. Therefore, 72% (44% + [28% x 2/3]) of the Delta farmers relied on both rented and owned substantially or on totally rented lands for their livelihood.

According to the Stanford Research Institute, in the Mekong Delta, landlords supplied virtually no credit, seeds, fertilizer, farm implements but usually collected rents in kind in the form of one third or more of the harvest, which was usually fixed in advance. It did not matter whether the harvest was good or bad. If the harvest was bad due to bad weather or insect or disease damage, the tillers still were responsible for the rent. If they could not pay, interest as high as 60% a year would be applied to what they owed, and lead to as much as three fourths of the harvest collected in the next harvest.

Landlords of at least more than half of the rented lands were mostly absentees living in France or in cities. At harvest time, landlords or their agents who usually were village notables or military officers would collect the rent due. These agents would have a cut (15-20%) of what they could collect. Therefore, coercive methods were often used, leading to a lot of resentment.

Farmers also suffered from selling their rice crops at a fixed price to local middlemen, usually the Chinese operator of the local grocery store who advanced the farmers the money or the groceries his family needed to live on until harvest time or to hire needed labor, or to acquire agri-inputs.

In the Central Lowlands, with scarcity of lands, the situation was a lot worse. There, only 190,000 families (or 27%) out of 695,000 owned an average of 1.5 acres (or 0.6 ha) of the land they tilled. The majority or 403,000 farming families (or 58%) tilled two acres (0.8 ha) with half of that land rented from someone else. A minority of 74,000 farmers rented the average of one acre (0.4 ha) of land they farmed. Rents in the area amounted to 50% of the harvest.

With this sad state of affairs in our rural society, one could easily understand why it was easy for the communists to foment insurgency warfare. We could readily deal with an aggression war from the North, but having an internal insurgency war in the countryside where disaffected peasants sheltered and supported the guerillas with food and manpower on top of that would make things so much more difficult to cope with. For this reason, President Thieu realized that he must transform our rural society by changing it into an ownership society to give the poorest and most numerous segment of our population a chance to break out of its grinding cycle of poverty. In other words, he must bring about a rural revolution using land reform and agricultural development to win back the heart and mind of the majority of the South Vietnamese people who lived and worked in the countryside. President Thieu and his close advisor on agrarian reform and economic development, Mr. Cao Van Than were visionary enough to realize that here was no other way around that sad situation. They also were not under any illusion that this would not be a major and massive undertaking of epic proportion. And judging from past performance and the present political turmoil they entertained no notion that this would not be a highly intricate task nor something that could only be tackled at a more favorable time.

Background

First, it is worthwhile to go over some background information on land tenure throughout the ages in South Viet Nam to understand the rationale behind this vast undertaking. Land tenure management in Viet Nam went through many changes since time immemorial. Here are some important ones.

Dynastic Land Reforms:

Throughout most of our 2000 years of history the Viet Namese people had lived under different royal and imperial dynasties. During these feudal times, under the self- proclaimed mandate from heaven, emperors and kings literally owned all the country’s lands, which they doled out to mandarins, generals, and veterans as rewards for their past meritorious service and their unwavering allegiance to the empires or kingdoms. These rulers also accorded lands to newly created villages as source of their revenues to run their local government—these lands were known as communal lands (cong dien).

There was one noticeable land development scheme that resulted in the reclamation of large marginal swamp lands performed by Nguyen Cong Tru, a famous mandarin of the Nguyen Dynasty under Emperor Tu Duc. This project opened up new lands for the resettlement of a lot of landless people and for the creation of new villages. But we did not have too many of these undertakings in ancient times. The adventurous people themselves had to band themselves up and blaze trails in their southward migration to build new lives and new fortunes for themselves, most of the time at heavy cost of lives and limbs, in the last six centuries, much like the American pioneers in their westward movement.

All through successive dynasties, little ever changed except for minor tinkering in the creation of feudal societies where the lot of the peasants did not improve much through the ages.

Land Management under the French Domination:

Then, beginning in the 1860’s and in the early Twentieth Century under the French domination, the French colonialists allowed their citizens and the Viet Namese who served them in their administration, and thus deserved to acquire French citizenship, to exploit virgin lands for cultivation of both industrial plants (hemp, jute, sugar cane, tea, coffee, and rubber trees) and rice or secondary crops (beans, peanut). The colonial administration also used public funds to finance vast land reclamation schemes and private citizens who disposed of means could buy these lands at auctions upon completion of the project. Of course, these auctions were out of the reach of common poor people.

Consequently, newly cleared lands were usually bought exclusively by the rich, famous, influential, and powerful people in our society. South Viet Nam had roughly 15,000,000 acres (6,000,000 ha) of cultivable lands. Half of that total or 7,500,000 acres (3,000,000 ha) was under cultivation and was owned by some 50,000 landowners of all sizes. Some 6,000 largest landowners possessed nearly 3,000,000 acres (1,200,000 ha) or 40% of the cultivated land. In the Mekong Delta alone, 430 French citizens owned 625,000 acres (250,000 ha) or more 8% of the total land under cultivation.

I need to open some big parentheses here to give the readers some insight as to why land reform was not successful during the First Republic and the Interregnum Period. I knew three of these French citizens mentioned above very well. They were brothers and were my great uncles Gaston Do Van Diem (Great Uncle Eighth) and Charles Do Van Kia Great Uncle Tenth), two former District Chiefs of many provinces in the Mekong Delta during the colonial time and the middle brother Do Van Son, my mom’s father, was also a former District Chief like his siblings. [Actually my Mom was born out of wedlock when her landlord father had an illicit affair with a beautiful daughter of one of his tenant farmers because his legal wife was sterile]. These three brothers rose to the top administrative rank of Doc Phu Su Dac Hang (Doc Phu Su Exceptional Class) in the late 30’s and early 40’s and were awarded the prestigious French Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honor) the highest civilian medal for their forty years of meritorious services for the colonial authorities. I was told that they were honored for having cleared hundreds of thousands of acres of rice land and dug hundreds of kilometers of canals and built thousands of kilometers of rural roads in their many Mekong Delta districts over these four decades of colonial service to be thus recognized. Naturally they themselves also owned thousands of acres of rice land each here and there in the Delta wherever they used to hold office. The Do’s clan was very big. It came from a Do ancestor who was a notable in the French colonial village administration in Chau Doc. He was the Chief of the Council of Notables (Hoi Dong Xa) of a village. He had nine children.

At the time my Mom sent me to Saigon for my high schooling I stayed the first six years in a house on 14 Nguyen Thanh Y Street in Dakao District of Saigon with Great Uncle Gaston Diem, the titular head of the clan because he was the oldest surviving son of the bunch. That clan had numerous descendants who were village administrators of various capacities throughout the Mekong Delta, especially in Chau Doc, An Giang, Dinh Tuong, Long An, Bac Lieu Provinces. It even had men who fought in France’s army against Hitler. It also sent a member to Paris as deputy from Cochinchina in the French General Assembly. Quite a few people in the clan married French men and women. It counted no less than three colonels [one, Colonel Hoang Van Ty who married my seventh aunt, was General Thieu’s second in command at the Dalat Military Academy] in the Republic of Viet Nam Army and Air Force assimilated from the French Armed Forces. It also had numerous lesser ranking officers in the RVNAF except Uncle Quang, the tenth son of my Great Uncle Do Van Diem. Nobody knew what got into him, but he joined the Viet Minh to fight the French. Of course, the communists did not trust people of his class, so he was only a medic in their forces. He came home quite disillusioned after Dien Bien Phu.

Every year the clan’s members gathered for ancestors’ worshipping a couple times at my great uncle’s house true to our Viet Namese tradition. All I heard vehemently discussed there by at least a couple hundred relatives was how to use all the loopholes there were in the land reform laws to keep the land in each descendant family. Uncle Four Nguyen Van Trinh, the Director General of Land Affairs (DGLA) and his son-in-law Dang who was the Provincial Land Affairs Service (PLAS) Chief in Go Cong Province held court in telling everybody what to do to fight expropriation, circumvent the regulations, and evade the laws or request for expropriation and compensation for land abandoned in remote areas or taken over by the VC’s. They were mostly absentee landlords at that time, living in France or in Saigon.

The powerful Do Clan was dead set against land reform because they thought it was unfair, illegal, and smacked of communist highhandedness and class warfare. When the French gave South Viet Nam independence after the Dien Bien Phu debacle they bought back all the rice lands owned by the French citizens to give to the government of Viet Nam, under Emperor Bao Dai as Chief of State with Ngo Dinh Diem as Prime Minister, supposedly to be distributed to landless farmers.

But somehow all my distant uncles and their descendants still had rice lands from the clan’s big holdings. I remember when my parents moved to Saigon in the late 50s they bought a unit of my great uncle Do Van Kia’s new three-story sixty-unit condo that he got from the French at the foot of the Hien Vuong Bridge in exchange for giving up a part of his land holdings. From my great uncle Do Van Diem came three interesting individuals who played some important roles in our regime’s history: 1) His son-in-law, Le Tan Nam who married his oldest daughter, held a few ministerial portfolios (mostly Ministry of Justice = Bo Tu Phap) early in Nguyen Van Tam’s, Tran Van Huu’s, and Ngo Dinh Diem’s administrations. He was the first Viet Namese to receive the French Licence-en-Droit (JD) and was Tan An District Chief and Saigon Mayor for many years; 2) Le Tan Nam’s son—Le Tan Loc was the perpetual Director General of Viet Nam Thuong Tin (Viet Nam Credit Bank), the big government bank; 3) Another son-in-law who married his third daughter, my uncle Nguyen Van Trinh, the DGLA who was in charge of implementing the Diem’s and the Interregnum Period’s agrarian reform programs. Obviously, it was a poor choice to pick a member of a big land-holding family who didn’t believe in agrarian reform to do land redistribution. Besides, a mandarin like President Diem would not be someone who would have a burning desire to redress social justice through meaningful, drastic, and revolutionary land reform. So, not much enthusiastic work had been done for more than a decade of land reform schemes, not to mention a lot of evasions of the law perpetrated by landowners through insider information.

That was why when Minister Cao Van Than was entrusted by President Thieu to implement his landmark Land To The Tiller Land Reform Program, a new landless young Northerner Director General of Land Affairs named Bui Huu Tien was put in charge of the DGLA and a brand new team of young and dynamic technocrats was put in place to carry out vigorously the hard and pressing work.

That did not mean that the Do Clan was not patriotic: it had two officers posthumously awarded the highest medal of valor of SVN, the Bao Quoc Quan Chuong, akin to the American Medal of Honor. My DGLA Chief uncle Nguyen Van Trinh’s oldest son who was my cousin and fellow J.J. Rousseau high school mate, Lt. J.G. Jean Nguyen Van Tri was the South Viet Namese second in command of one of our Navy ships that was sunk by the stronger Chinese communist naval forces during the naval engagement for the defense of the Paracels Islands on order from President Thieu.

He was mortally wounded by enemy’s rocket fire, rescued by his fellow combatants on a raft that was drifting in the South China Sea for almost a week before they were rescued by a foreign merchant ship. When his blood was attracting sharks that endangered his men and knowing that he would not survive, Tri ordered his men to toss him overboard to end his suffering. They refused to obey his order. They eventually had to do that after he died to get rid of the trailing sharks. Tri was one of the two South Viet Namese naval officers who were honored as national heroes by both our regime and the current communist regime for being killed in combat fighting the Chicoms. The other officer was another one of our ship commanders who was killed in the same battle. This was the famous battle discussed at the Cornell Symposium by Rear Admiral Nguyen Van Ky Thoai, Commander of that fateful MR I Naval Forces.

I relate this family story just to give you an insight on one of the reasons why President Diem’s land reform failed and to give a probable explanation as why only in Long An, An Giang, and Chau Doc Provinces, where most of the people of that clan exerted strong influence in the local government, almost half of all the grievances stemming from the Land To The Tiller Program (LTTTP) implementation originated. You can multiply this situation by at least 300 since there were that many similar clans in South Viet Nam to understand the magnitude of the obstacles President Thieu and Minister Than must have overcome to carry the Second Republic’s social revolution to satisfactory completion.

The French colonial administration unintentionally aggravated the land tenure problems by vastly increasing land holdings in the hands of a few powerful people, usually French citizens or Viet Namese having French citizenship by serving in their colonial administration or the village notables who governed the colony at the grassroots level. The French colonialists in power at the time did indeed open up vast areas of lands in their colony in the South through forest land clearings for industrial plantations and through swamp land reclamations in the Mekong Delta for rice farming. But these efforts did not benefit many landless farmers because the local authorities at different levels managed to amass through collusion, deception, ruse, trick, fraud the bulk of these lands for themselves.

Agrarian Reform Under the First Republic of Viet Nam:

Real agrarian reform was first approached under the First Republic of Viet Nam from 1955 to 1963. But that weak first attempt was an unworkable program following the promulgation of Ordinance 57 in October 1956, that achieved poor results. During these eight years, little was accomplished as expected, for one reason or another. A few plausible reasons were discussed above.

Before the events of Ordinance 57, there were two attempts by President Ngo Dinh Diem to control the excesses of the land tenancy system in South Viet Nam by controlling rents and by giving a greater degree of land tenure to tenant farmers. Ordinance 2, promulgated on January 28, 1955, mandated that land rent be between 15-25% of the average harvest and be formalized with a three-year written contract to reduce evictions. Ordinance 7, promulgated on February 5, 1955, was designed to protect the rights of tenants on new and abandoned lands to encourage cultivation (squatters’ rights protection). These ordinances also reduced rent payments after crop failure and gave renters first right of refusal should the owners decide to sell their holdings.

Now let’s take a closer look at land reform under the First Republic of Viet Nam, the first weak attempt at real reform of land tenure. Unfortunately this was not done the right way! Otherwise, we probably would not have to fight the Viet Nam War as Roy Prosterman and Chester Bowles said. That lost decade between 1954 to 1964 and the following Interregnum Period between 1964 to 1967 could have been used effectively to launch a rural social revolution similar to the one President Nguyen Van Thieu implemented sixteen years later complete with a vigorous agriculture-based economic development program. The ensuing transformation of the South Viet Namese society would be such that it could have very well pre-emptd any NVN’ s attempt to subvert SVN free government and its stronger economy. It was a terrible missed opportunity that led to horrific consequences for tens of millions of South Vietnamese!

In a nutshell, the legal basis of the First Republic of Viet Nam land reform program was covered by Ordinance 57 signed by President Ngo Dinh Diem in October of 1957. It put a 250-acre (100 ha) limit on rice land ownership and gave the landlords the right to keep another 37.5 acres (fifteen ha) for ancestral worship. Any excess land would be expropriated and owners would be compensated. Expropriated land would then be sold to farmers in installments. Landowners received ten per cent of land price in cash and ninety per cent in government bonds redeemable in twelve years. The huge 250-acre cap left only 1,130,000 acres (452,000 ha), which made up only twenty % of SVN domestically owned lands, available for expropriation from some 2,035 landlords. These lands were usually not prime rice lands because the landowners claimed the best lands as their 250 acres (100 ha) retained property for themselves or their relatives or their 37.50 acres (fifteen ha) of ancestral worship land: These expropriated lands were usually not the best rice lands near rivers, canals, and rural roads, but were abandoned lands in remote areas or cultivated lands in communist-controlled areas from which landlords could not collect rent anyway or lands far away from transportation networks. On the other hand, the prime land that each landowner was allowed to keep—287.5 acres—would continue to keep up to eighty tenant farmers in perpetual bondage because the average rented plot of land was 3.5 acres (1.4 ha) in the Delta.

At that time, the government also disposed of two other chunks of public domain lands that it did a pretty poor job of redistribution to needy and deserving tilling farmers: 1) 662,000 acres (265,000 ha) “squatter claimed” lands; 2) 375,000 acres (150,000 ha) of “land development center” agricultural lands.

The program had so many loopholes that were easily exploited by devious landlords and sharp lawyers to avoid expropriation. Prosterman and Riedinger gave an excellent study of these problems in their “Land Reform and Democratic Development” book for anyone interested in a deeper understanding of this program.

As Roy Prostetrman et al reported, “…The cumulative result of all the program as of the end of 1967 was the distribution of some 275,000 hectares (687,000 acres) of land to 130,000 families. This represented less than 1/8 of SVN cultivated land, with benefits going to barely 1/10 of those who had been wholly or substantially dependent on farming land as tenants.”

Now, just what exactly was accomplished during those seven years under the Diem Administration?

Because of the adoption of complex and centralized bureaucratic procedures for the distribution processes, from 1957 to 1963, only fifty per cent of expropriated lands were redistributed or roughly 560,000 acres (226,000 ha). Understandably, poor farmers had little money to buy necessities of life much less to buy lands. So, only roughly 100,000 out of approximately 1,000,000 existing tenant farmers (almost all in the Mekong Delta) benefitted from the program. (The 900,000 difference will be discussed below). The 625,000 acres (250,000 ha) of French citizens’ lands was barely touched because only fewer than 12,500 acres (5,000 ha) were distributed to 2,900 families, mainly in Ninh Thuan and Binh Thuan Provinces. The difference between the results achieved at the end of 1967 and 1963 was the result in land distribution achieved during the Interregnum Period: 687,000 – 560,000 = 127,000 acres (275,000 – 226,000 = 49,000 ha) given to 130,000 – 100,000 = 30,000 families. This period was a period of chaotic government due to military coup after military coup and a time of increasing insurgency war fomented and perpetrated by the communist North Vietnamese.

So the political, social, and economic impact of this land reform was minimal and inconsequential. That was why the insurgency war intensified during this time. The battle for the hearts and minds of the South Vietnamese people could not be won. And President Diem tried other ineffective and costly schemes like agro-villes to change the countryside to no avail.

Shortly after he became Chief of State, President Thieu realized that to prosecute the war against the communists effectively he had to focus on land reform a lot more than the previous administration. On September 1968, he began to formulate and enunciate his own concept of land reform by giving an accurate assessment of the situation: The government of the RVN was faced with a long standing problem of social injustice which demanded solution if the pacification was to be effective. The practice of tenant farming, which in effect, made the tenant farmer slave to the land and to a continuous cycle of poverty, had to be abolished. This was a monumental historical decision of epic proportion by a leader of Viet Nam.

President Thieu hoped to achieve three main goals with the transformational land reform program he contemplated:

1. Provide social justice for the long suffering Viet Namese peasants

2. Undercut the Viet Cong land distribution scheme to gain the political support needed to establish government control of the countryside

3. Provide the basis for a sound agricultural economy

That brings me to a detailed discussion of land reform under the Second Republic of Viet Nam that I had first-hand knowledge with when I was the Director of Cabinet—the third highest-ranking official of the ministry--of Minister Cao Van Than, the new dynamic, hard-working, driven, and knowledgeable Minister of Land Reform and Agriculture Development, a close Adviser of President Thieu in agrarian reform and economic development, the architect, and the implementer of the most successful land reform program of all time in recent history. It was the kind of land reform program that the New York Times unabashedly called ”probably the most ambitious and progressive non-Communist land reform of the twentieth century.” From a leftist newspaper, this was an unadulterated compliment.

Land Tenure in South Viet Nam:

Before going into the details of President Thieu’s land reform program, it is a good idea to cover the state of land tenure prevalent at the time when President Thieu proclaimed the Second Republic of Viet Nam in 1967.

At that time, some 60% of the South Viet Namese population of roughly 17,000,000 were peasants or a little more than 10,000,000. They were mainly rice farmers. And three fifths (3/5) of these farmers or roughly 6,000,000 lived in the Mekong Delta where 80% of rice was produced. The remaining two fifths (2/5) of the farmers or roughly 4,000,000 lived in the narrow coastal plains of the Central Lowlands.

According to available statistics from UN/FAO, in the early 1960s there were 1,175,000 farming households, but only 257,000 (or 22%) farming families owned all their lands in mainly the Mekong Delta. Their average acreage was roughly four acres (1.7 hectares). Another 334,000 families (or 28%) farmed an average of six acres (2.4 ha) of rice land both rented and owned: with 2/3 of total area rented from landlords and 1/3 of the area owned. There were 521,000 farming families (or 44%) who farmed an average of 3.5 acres (1.4 ha) of lands that was totally rented from landlords. Therefore, 72% (44% + [28% x 2/3]) of the Delta farmers relied on both rented and owned substantially or on totally rented lands for their livelihood.

According to the Stanford Research Institute, in the Mekong Delta, landlords supplied virtually no credit, seeds, fertilizer, farm implements but usually collected rents in kind in the form of one third or more of the harvest, which was usually fixed in advance. It did not matter whether the harvest was good or bad. If the harvest was bad due to bad weather or insect or disease damage, the tillers still were responsible for the rent. If they could not pay, interest as high as 60% a year would be applied to what they owed, and lead to as much as three fourths of the harvest collected in the next harvest.

Landlords of at least more than half of the rented lands were mostly absentees living in France or in cities. At harvest time, landlords or their agents who usually were village notables or military officers would collect the rent due. These agents would have a cut (15-20%) of what they could collect. Therefore, coercive methods were often used, leading to a lot of resentment.

Farmers also suffered from selling their rice crops at a fixed price to local middlemen, usually the Chinese operator of the local grocery store who advanced the farmers the money or the groceries his family needed to live on until harvest time or to hire needed labor, or to acquire agri-inputs.

In the Central Lowlands, with scarcity of lands, the situation was a lot worse. There, only 190,000 families (or 27%) out of 695,000 owned an average of 1.5 acres (or 0.6 ha) of the land they tilled. The majority or 403,000 farming families (or 58%) tilled two acres (0.8 ha) with half of that land rented from someone else. A minority of 74,000 farmers rented the average of one acre (0.4 ha) of land they farmed. Rents in the area amounted to 50% of the harvest.

With this sad state of affairs in our rural society, one could easily understand why it was easy for the communists to foment insurgency warfare. We could readily deal with an aggression war from the North, but having an internal insurgency war in the countryside where disaffected peasants sheltered and supported the guerillas with food and manpower on top of that would make things so much more difficult to cope with. For this reason, President Thieu realized that he must transform our rural society by changing it into an ownership society to give the poorest and most numerous segment of our population a chance to break out of its grinding cycle of poverty. In other words, he must bring about a rural revolution using land reform and agricultural development to win back the heart and mind of the majority of the South Vietnamese people who lived and worked in the countryside. President Thieu and his close advisor on agrarian reform and economic development, Mr. Cao Van Than were visionary enough to realize that here was no other way around that sad situation. They also were not under any illusion that this would not be a major and massive undertaking of epic proportion. And judging from past performance and the present political turmoil they entertained no notion that this would not be a highly intricate task nor something that could only be tackled at a more favorable time.

BUILDING AN OWNERSHIP SOCIETY FOR A RURAL SOCIAL REVOLUTION (III)

Implementation

To implement the LTTTP the following steps were taken:

1. Our MLRAD developed a detailed implementation plan and reorganized the division in charge, its Directorate General of Land Affairs (DGLA) from the highest to the lowest echelons, from central to local levels along the paper trail in order to execute the plan smoothly and rapidly. We also created a Regional Office in the Mekong Delta where 80% of the work would be carried out to speed up the liquidation of problems that could be solved by mid-level authority instead of channeling them all the way to central authority in Saigon. This would be a great time-saver at a time when communication was slow and transportation was scarce. Without this we would never be able to finish the job as fast as we did. At a time and in a country where people tended to concentrate authority to a few high officials, it was a credit to Minister Than’s organizational genius that we adopted this decentralization of power. We also created new organizations that would perform the inspection and investigation functions to make sure that the proper procedures and the right amount of work would be done according to the implementation plan laid out from central to regional on to provincial, all the way down to local riceroots levels. These organizations luckily were staffed by young dynamic and fearless technocrats, most of the time just right out of colleges. So their sense of duty was very high and their performance consequentially was very efficient as compared to those of an ingrained bureaucracy. You cannot do any effective work, especially the kind that requires timely coordination of a multitude of implementing set-up without good and strong investigative and inspective functions. These beefed-up organizations would handle the expected increased number of grievances and inquiries from all sides – tenant farmers and landowners and sudden flood of work volume.

2. It was a stroke of genius on our part to adopt the unprecedented use of aerial photography to help map out and identify the land plots to be distributed with the provision that accurate official cadastral maps produced with surveying equipments would be done some time in the future to formalize and legalize the photo mapping when such work can be done at a leisurely pace. Otherwise, it would take decades to finish this gigantic program with conventional cadastral ways and means, especially when the country was caught in the middle of upsetting vagaries of war.

3. The program called for also the extensive training of some 50,000 government employees at all levels on technical, procedural, and administrative issues. The MLRAD cadres were trained in house in land reform and land affairs by the DGLA. The Rural Development Cadres of the Ministry of Rural Reconstruction (renamed Ministry of Revolutionary Development in 1969) were trained in rural pacification and rural development at their sprawling Vung Tau Training Center run by Colonel Nguyen Van Be, a VC returnee who was very good at training cadres in doing things to defuse, deflect, derail, dismantle, decapitate, demolish, defeat, and destroy communist tactics and strategies in the countryside. Later they would be trained in land reform procedures on site by the DGLA technocrats and local authorities. The CIA supported his activities by building near Vung Tau a vast training complex for that purpose,