--Liên Hiệp Quốc chỉ trích Việt Nam trục xuất người tị nạn

Việt Nam và Thái Lan, ngày 20/11/2015, đã bị Liên Hiệp Quốc chỉ trích vì đã trục xuất người tị nạn. Theo tổ chức quốc tế này, những người bị trao tra có nguy cơ bị “vi phạm nghiêm trọng nhân quyền”.

Theo tuyên bố của bà Ravina Shamdasani, phát ngôn viên Phủ Cao ủy Nhân quyền Liên Hiệp Quốc với giới báo chí, trong tháng 10/2015, Việt Nam đã bắt giam 9 công dân Bắc Triều Tiên, trong đó có một em bé một tuổi và một thiếu niên. Những người này sau đó đã được chuyển cho chính quyền Trung Quốc – đồng minh chính của Bình Nhưỡng.

Bà Shamdasani lo sợ rằng “những người này có thể đã bị trả về Cộng hòa Dân chủ Nhân dân Triều Tiên. Họ có nguy cơ bị vi phạm nhân quyền trầm trọng”. Theo nội dung báo cáo, nhóm người này đến từ thành phố Thẩm Dương, gần với biên giới Bắc Triều Tiên và họ bị bắt tại Việt Nam ngày 22/10/2015. Sau đó những người này đã được trả về cho chính quyền thành phố Đông Hưng, gần với biên giới Việt Nam.

Cũng theo phát ngôn viên của Liên Hiệp Quốc, dường như “nhóm người này đã được chính quyền Bắc Kinh hộ tống đưa đi đâu không ai rõ”. Bà Shamdasani quan ngại là “chín người này có thể đã bị cưỡng bức hồi hương”.

Tuyên bố trên của bà Shamdasani được đưa ra ngay sau khi Đại Hội Đồng Liên Hiệp Quốc lên án các “ hành động vi phạm nhân quyền phổ biến, liên tục và có hệ thống lâu nay tại Bắc Triều Tiên”.

Ngoài ra, phát ngôn viên Phủ Cao ủy Nhân quyền Liên Hiệp Quốc cũng chỉ trích Thái Lan đã trục xuất không rõ lý do hai công dân Trung Quốc, đã được công nhận quy chế tị nạn, được quyền hưởng chế độ tái định cư ở nước thứ ba.

Phát ngôn viên Phủ Cao ủy tị nạn lấy làm quan ngại rằng “hành động này của Thái Lan chỉ xảy ra vài tháng sau khi nước này bị chỉ trích mạnh mẽ vụ trục xuất 109 người Duy Ngô Nhĩ, một sắc tộc thiểu số theo đạo Hồi tại Trung Quốc”.

Bà Shamdasani nhắc lại là: “Nguyên tắc không trao trả nghiêm cấm việc cưỡng bức hồi hương một người tị nạn đến từ một quốc gia mà ở đó họ có thể phải đối mặt với các hành động đàn áp hay tra tấn. Nguyên tắc này đã được ghi trong điều khoản 3 của Hiệp ước chống Tra tấn hay những hành động Đối xử hoặc Trừng phạt bạo tàn, vô nhân đạo hay gây tổn thương khác, mà Thái Lan vẫn thường hay sử dụng”.

Cuối cùng, bà Shamdasani kêu gọi chính phủ Việt Nam và Trung Quốc làm rõ số phận những người Bắc Triều Tiên nói trên, đồng thời kêu gọi cả hai chính phủ nên hạn chế việc cưỡng bức hồi hương những công dân bỏ trốn khỏi Bắc Triều Tiên.

- VN ‘bắt nhà hoạt động giúp tỵ nạn Bắc Hàn’ — (BBC).

Hàng trăm người đã tới Hàn Quốc từ Việt Nam

Các hãng thông tấn đưa tin một nhà hoạt động Hàn Quốc chuyên giúp người tỵ nạn Bắc Hàn đào tẩu vừa bị bắt hồi tuần trước tại TP. Hồ Chí Minh.

Hãng tin Pháp AFP dẫn nguồn Bộ Ngoại giao Hàn Quốc nói người này bị giới chức Việt Nam bắt vì giúp người Bắc Hàn chạy tới Nam Hàn qua con đường Việt Nam.

Phát ngôn viên của bộ này nói với AFP rằng người đàn ông họ là Yoo, 51 tuổi, bị "nhân viên an ninh" bắt tại một khách sạn ở TP Hồ Chí Minh vào thứ Tư tuần trước 13/6.

Trong khi đó, thông tấn xã Hàn Quốc Yonhap, dẫn lời quan chức sứ quán Hàn Quốc tại Hà Nội, xác nhận ông Yoo bị bắt vì "công việc giúp người tỵ nạn", nhưng không rõ chính xác là công việc gì.

Cho tới nay, chính phủ Việt Nam chưa đưa ra lý do cho vụ bắt ông Yoo vì quá trình điều tra còn tiếp diễn.

Bộ Ngoại giao Hàn Quốc cũng đã yêu cầu được phỏng vấn ông.

Các kênh chính thức của Việt Nam không hề có tin tức gì về vụ bắt giữ này.

Hàn Quốc là đích đến của đa số, tới nay con số người Bắc Hàn đào tẩu xuống miền Nam đã lên tới trên 20.000.

Tuy nhiên để đến được Hàn Quốc, người Bắc Hàn thường phải qua một hay nhiều nước thứ ba khác, như Trung Quốc và các quốc gia Đông Nam Á.

Từ khi Trung Quốc siết chặt quản lý biên giới và trục xuất tất cả người tỵ nạn Bắc Hàn bắt được tại nước này, dòng người tỵ nạn chuyển sang các nước phía Nam, trong đó có Việt Nam, gây khá nhiều rắc rối về ngoại giao.

Năm 2004, khoảng 400 người tỵ nạn Bắc Hàn đã được chuyển từ Việt Nam tới Hàn Quốc trong một sự kiện thu hút nhiều chú ý.

Việt Nam không muốn tạo tiền lệ trở thành điểm trung chuyển của người tỵ nạn Bắc Hàn, và cũng không muốn gây căng thẳng với Bình Nhưỡng.

Thế nhưng Hàn Quốc là nước đầu tư nhiều vào Việt Nam, và Hà Nội cũng muốn giữ quan hệ tốt với Seoul.

Đa phần các cuộc đào tẩu của người Bắc Hàn đều có sự liên quan giúp đỡ của các nhà hoạt động Nam Hàn.

- VN ‘bắt nhà hoạt động giúp tỵ nạn Bắc Hàn’ — (BBC).

-Trung Quốc quyết định viện trợ Bắc Hàn-30.01.12 -– Trung Quốc viện trợ Triều Tiên không điều kiện (NLĐ).- Nga đồng ý xóa 90% nợ thời Liên Xô cho Triều Tiên (TTXVN). -- Nga: “Tân quan tân chính sách” với chương trình tư nhân hóa

Nga: “Tân quan tân chính sách” với chương trình tư nhân hóa

-, 'Việt Nam cần có trách nhiệm với Bắc Hàn'-10.01.12

-, Người tỵ nạn Bắc Hàn đi Hàn Quốc-20.10.09

-Người Bắc Hàn chờ tị nạn ở HN-25.09.09

-, Người Bắc Hàn xin tị nạn ở Hà Nội-24.09.09

- Câu chuyện tị nạn của một giáo dân Cồn Dầu — (NV).

- Hiểm họa tham nhũng ở Trung Quốc: Nghịch lý song song (NNVN).

-

China News: Một góc đáy xã hội Trung Quốc qua ảnh

Tranh giành quyền lực ở Trung Quốc: Children of Mao's wrath vie for power in China (Reuters 22-6-12)◄--Bắc Kinh bắt đầu kiểm duyệt South China Morning Post? Hong Kong Newspaper Charged With Downplaying Dissident’s Death (Reuters NYT 21-6-12)

Vụ Bạc Hi Lai - Từ Minh: A Tycoon Rises and Falls With a Chinese Leader (WSJ 22-6-12)-Báo Nhật: Vợ Bạc Hy Lai thừa nhận giết doanh nhân Anh

- Cao Ủy Tị Nạn LHQ bổ nhiệm phụ nữ Việt làm đại diện tại Úc — (NV).

Tại sao Trung Quốc sẽ không sụp đổ? Why China Won't Collapse (National Interest 22-6-12) -- Phải nghiến răng mà đọc! (Thằng cha này là giảng viên về Triết học tây phương ở Đại học Thanh Hoa)

E-marketing - Để dạy học: E-Tailer Customization: Convenient or Creepy? (NYT 23-6-12)

-Arts & Letters Daily (25 Jun 2012)

-More than 12 million civilians were expelled from their birthplaces; at least 500,000 died: This is the European atrocity you never heard about... more

June 11, 2012

The European Atrocity You Never Heard About

By R.M. Douglas

The screams that rang throughout the darkened cattle car crammed with deportees, as it jolted across the icy Polish countryside five nights before Christmas, were Dr. Loch's only means of locating his patient. The doctor, formerly chief medical officer of a large urban hospital, now found himself clambering over piles of baggage, fellow passengers, and buckets used as toilets, only to find his path blocked by an old woman who ignored his request to move aside. On closer examination, he discovered that she had frozen to death.

Finally he located the source of the screams, a pregnant woman who had gone into premature labor and was hemorrhaging profusely. When he attempted to move her from where she lay into a more comfortable position, he found that "she was frozen to the floor with her own blood." Other than temporarily stanching the bleeding, Loch was unable to do anything to help her, and he never learned whether she had lived or died. When the train made its first stop, after more than four days in transit, 16 frost-covered corpses were pulled from the wagons before the remaining deportees were put back on board to continue their journey. A further 42 passengers would later succumb to the effects of their ordeal, among them Loch's wife.

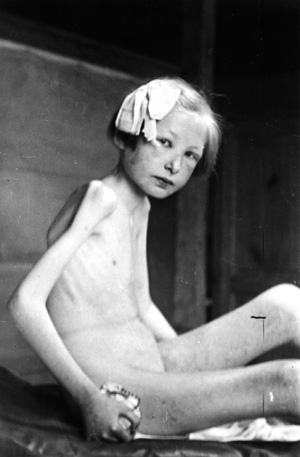

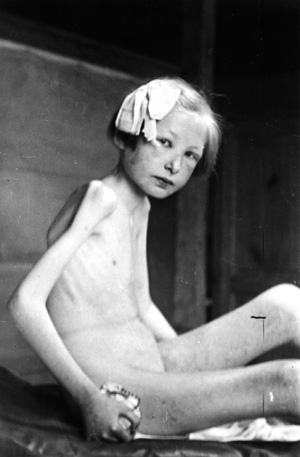

Hoover Institution Archives

An estimated 500,000 people died in the course of the organized expulsions; survivors were left in Allied-occupied Germany to fend for themselves.

During the Second World War, tragic scenes like those were commonplace, as Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin moved around entire populations like pieces on a chessboard, seeking to reshape the demographic profile of Europe according to their own preferences. What was different about the deportation of Loch and his fellow passengers, however, was that it took place by order of the United States and Britain as well as the Soviet Union, nearly two years after the declaration of peace.

Between 1945 and 1950, Europe witnessed the largest episode of forced migration, and perhaps the single greatest movement of population, in human history. Between 12 million and 14 million German-speaking civilians—the overwhelming majority of whom were women, old people, and children under 16—were forcibly ejected from their places of birth in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, and what are today the western districts of Poland. As The New York Times noted in December 1945, the number of people the Allies proposed to transfer in just a few months was about the same as the total number of all the immigrants admitted to the United States since the beginning of the 20th century. They were deposited among the ruins of Allied-occupied Germany to fend for themselves as best they could. The number who died as a result of starvation, disease, beatings, or outright execution is unknown, but conservative estimates suggest that at least 500,000 people lost their lives in the course of the operation.

Most disturbingly of all, tens of thousands perished as a result of ill treatment while being used as slave labor (or, in the Allies' cynical formulation, "reparations in kind") in a vast network of camps extending across central and southeastern Europe—many of which, like Auschwitz I and Theresienstadt, were former German concentration camps kept in operation for years after the war. As Sir John Colville, formerly Winston Churchill's private secretary, told his colleagues in the British Foreign Office in 1946, it was clear that "concentration camps and all they stand for did not come to an end with the defeat of Germany." Ironically, no more than 100 or so miles away from the camps being put to this new use, the surviving Nazi leaders were being tried by the Allies in the courtroom at Nuremberg on a bill of indictment that listed "deportation and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population" under the heading of "crimes against humanity."

By any measure, the postwar expulsions were a manmade disaster and one of the most significant examples of the mass violation of human rights in recent history. Yet although they occurred within living memory, in time of peace, and in the middle of the world's most densely populated continent, they remain all but unknown outside Germany itself. On the rare occasions that they rate more than a footnote in European-history textbooks, they are commonly depicted as justified retribution for Nazi Germany's wartime atrocities or a painful but necessary expedient to ensure the future peace of Europe. As the historian Richard J. Evans asserted in In Hitler's Shadow(1989) the decision to purge the continent of its German-speaking minorities remains "defensible" in light of the Holocaust and has shown itself to be a successful experiment in "defusing ethnic antagonisms through the mass transfer of populations."

Even at the time, not everyone agreed. George Orwell, an outspoken opponent of the expulsions, pointed out in his essay "Politics and the English Language" that the expression "transfer of population" was one of a number of euphemisms whose purpose was "largely the defense of the indefensible." The philosopher Bertrand Russell acidly inquired: "Are mass deportations crimes when committed by our enemies during war and justifiable measures of social adjustment when carried out by our allies in time of peace?" A still more uncomfortable observation was made by the left-wing publisher Victor Gollancz, who reasoned that "if every German was indeed responsible for what happened at Belsen, then we, as members of a democratic country and not a fascist one with no free press or parliament, were responsible individually as well as collectively" for what was being done to noncombatants in the Allies' name.

That the expulsions would inevitably cause death and hardship on a very large scale had been fully recognized by those who set them in motion. To a considerable extent, they were counting on it. For the expelling countries—especially Czechoslovakia and Poland—the use of terror against their German-speaking populations was intended not simply as revenge for their wartime victimization, but also as a means of triggering a mass stampede across the borders and finally achieving their governments' prewar ambition to create ethnically homogeneous nation-states. (Before 1939, less than two-thirds of Poland's population, and only a slightly larger proportion of Czechoslovakia's, consisted of gentile Poles, Czechs, or Slovaks.)

For the Soviets, who had "compensated" Poland for its territorial losses to the Soviet Union in 1939 by moving its western border more than 100 miles inside German territory, the clearance of the newly "Polish" western lands and the dumping of their millions of displaced inhabitants amid the ruins of the former Reich served Stalin's twin goals of impeding Germany's postwar recovery and eliminating any possibility of a future Polish-German rapprochement. The British viewed the widespread suffering that would inevitably attend the expulsions as a salutary form of re-education of the German population. "Everything that brings home to the Germans the completeness and irrevocability of their defeat," Deputy Prime Minister Clement Richard Attlee wrote in 1943, "is worthwhile in the end." And the Americans, as Laurence Steinhardt, ambassador to Prague, recorded, hoped that by displaying an "understanding" and cooperative attitude toward the expelling countries' desire to be rid of their German populations, the United States could demonstrate its sympathy for those countries' national aspirations and prevent them from drifting into the Communist orbit.

The Allies, then, knowingly embarked on a course that, as the British government was warned in 1944 by its own panel of experts, was "bound to cause immense suffering and dislocation." That the expulsions did not lead to the worst consequences that could be expected from the chaotic cattle drive of millions of impoverished, embittered, and rootless deportees into a war-devastated country that had nowhere to put them was due to three main factors.

The first was the skill with which the postwar German chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, drew the expellees into mainstream politics, defusing the threat of a potentially radical and disruptive bloc. The second was the readiness of most expellees—the occasionally crass or undiplomatic statements of their leaders notwithstanding—to renounce the use or threat of force as a means of redressing their grievances. The third, and by far the most important, was the 30-year-long "economic miracle" that made possible the housing, feeding, and employment of the largest homeless population with which any industrial country has ever had to contend. (In East Germany, on the other hand, the fact that the standard of living for the indigenous population was already so low meant that the economic gap between it and the four million arriving expellees was more easily bridged.)

The downside of "economic miracles," though, is that, as their name suggests, they can't be relied upon to come along where and when they are most needed. By extraordinary good fortune, the Allies avoided reaping the harvest of their own recklessness. Nonetheless, the expulsions have cast a long and baleful shadow over central and southeastern Europe, even to the present day. Their disruptive demographic, economic, and even—as Eagle Glassheim has pointed out—environmental consequences continue to be felt more than 60 years later. The overnight transformation of some of the most heterogeneous regions of the European continent into virtual ethnic monoliths changed the trajectory of domestic politics in the expelling countries in significant and unpredicted ways. Culturally, the effort to eradicate every trace of hundreds of years of German presence and to write it out of national and local histories produced among the new Polish and Czech settler communities in the cleared areas what Gregor Thum has described as a state of "amputated memory." As Thum shows in his groundbreaking study of postwar Wroclaw—until 1945 and the removal of its entire population, the German city of Breslau—the challenge of confronting their hometown's difficult past is one that post-Communist Wroclawites have only recently taken up. In most other parts of Central Europe, it has hardly even begun.

Still less so in the English-speaking world. It is important to note that the expulsions are in no way to be compared to the genocidal Nazi campaign that preceded them. But neither can the supreme atrocity of our time become a yardstick by which gross abuses of human rights are allowed to go unrecognized for what they are. Contradicting Allied rhetoric that asserted that World War II had been fought above all to uphold the dignity and worth of all people, the Germans included, thousands of Western officials, servicemen, and technocrats took a full part in carrying out a program that, when perpetrated by their wartime enemies, they did not hesitate to denounce as contrary to all principles of humanity.

The degree of cognitive dissonance to which this led was exemplified by the career of Colonel John Fye, chief U.S. liaison officer for expulsion affairs to the Czechoslovak government. The operation he had helped carry out, he acknowledged, drew in "innocent people who had never raised so much as a word of protest against the Czechoslovak people." To accomplish it, women and children had been thrown into detention facilities, "many of which were little better than the ex-German concentration camps." Yet these stirrings of unease did not prevent Fye from accepting a decoration from the Prague government for what the official citation candidly described as his valuable services "in expelling Germans from Czechoslovakia."

Today we have come not much further than Fye did in acknowledging the pivotal role played by the Allies in conceiving and executing an operation that exceeded in both scale and lethality the violent breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. It is unnecessary to attribute this to any "taboo" or "conspiracy of silence." Rather, what is denied is not the fact of the expulsions themselves, but their significance.

Many European commentators have maintained that to draw attention to them runs the risk of diminishing the horror that ought properly to be reserved for the Holocaust and other Nazi atrocities, or giving rise to a self-pitying "victim" mentality among today's generation of Germans, for whom the war is an increasingly distant memory. Czechs, Poles, and citizens of other expelling states fear the legal ramifications of a re-examination of the means by which millions of erstwhile citizens of those countries were deprived of their nationality, liberty, and property. To this day, the postwar decrees expropriating and denationalizing Germans remain on the statute book of the Czech Republic, and their legality has recently been reaffirmed by the Czech constitutional court.

Some notable exceptions aside, like T. David Curp, Matthew Frank, and David Gerlach, English-speaking historians—out of either understandable sympathy for Germany's victims or reluctance to complicate the narrative of what is still justifiably considered a "good war"—have also not been overeager to delve into the history of a messy, complex, morally ambiguous, and politically sensitive episode, in which few if any of those involved appear in a creditable light.

By no means are all of these concerns unworthy ones. But neither are they valid reasons for failing to engage seriously with an episode of such obvious importance, and to integrate it within the broader narrative of modern European history. For historians to write—and, still worse, to teach—as though the expulsions had never taken place or, having occurred, are of no particular significance to the societies affected by them, is both intellectually and pedagogically unsustainable.

The fact that population transfers are currently making a comeback on the scholarly and policy agenda also suggests that we should scrutinize with particular care the most extensive experiment made with them to date. Despite the gruesome history, enthusiasts continue to chase the mirage of "humane" mass deportations as a means of resolving intractable ethnic problems. Andrew Bell-Fialkoff, in a much-cited study, has advocated population transfers as a valuable tool so long as they are "conducted in a humane, well-organized manner, like the transfer of Germans from Czechoslovakia by the Allies in 1945-47." John Mearsheimer, Chaim Kaufmann, Michael Mann and others have done likewise.

Few wars today, whether within or between states, do not feature an attempt by one or both sides to create facts on the ground by forcibly displacing minority populations perceived as alien to the national community. And although the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court has attempted to restrain this tendency by prohibiting mass deportations, Elazar Barkan maintains that such proscriptions are far from absolute, and that "today there is no single code of international law that explicitly outlaws population transfers either in terms of group or individual rights protections."

The expulsion of the ethnic Germans is thus of contemporary as well as historical relevance. At present, though, the study of many vital elements of this topic is still in its earliest stages. Innumerable questions—about the archipelago of camps and detention centers, the precise number and location of which are still undetermined; the sexual victimization of female expellees, which was on a scale to rival the mass rapes perpetrated by Red Army soldiers in occupied Germany; the full part played by the Soviet and U.S. governments in planning and executing the expulsions—remain to be fully answered. At a moment when the surviving expellees are passing away and many, though far from all, of the relevant archives have been opened, the time has come for this painful but pivotal chapter in Europe's recent history to receive at last the scholarly attention it deserves.

Việt Nam và Thái Lan, ngày 20/11/2015, đã bị Liên Hiệp Quốc chỉ trích vì đã trục xuất người tị nạn. Theo tổ chức quốc tế này, những người bị trao tra có nguy cơ bị “vi phạm nghiêm trọng nhân quyền”.

Theo tuyên bố của bà Ravina Shamdasani, phát ngôn viên Phủ Cao ủy Nhân quyền Liên Hiệp Quốc với giới báo chí, trong tháng 10/2015, Việt Nam đã bắt giam 9 công dân Bắc Triều Tiên, trong đó có một em bé một tuổi và một thiếu niên. Những người này sau đó đã được chuyển cho chính quyền Trung Quốc – đồng minh chính của Bình Nhưỡng.

Bà Shamdasani lo sợ rằng “những người này có thể đã bị trả về Cộng hòa Dân chủ Nhân dân Triều Tiên. Họ có nguy cơ bị vi phạm nhân quyền trầm trọng”. Theo nội dung báo cáo, nhóm người này đến từ thành phố Thẩm Dương, gần với biên giới Bắc Triều Tiên và họ bị bắt tại Việt Nam ngày 22/10/2015. Sau đó những người này đã được trả về cho chính quyền thành phố Đông Hưng, gần với biên giới Việt Nam.

Cũng theo phát ngôn viên của Liên Hiệp Quốc, dường như “nhóm người này đã được chính quyền Bắc Kinh hộ tống đưa đi đâu không ai rõ”. Bà Shamdasani quan ngại là “chín người này có thể đã bị cưỡng bức hồi hương”.

Tuyên bố trên của bà Shamdasani được đưa ra ngay sau khi Đại Hội Đồng Liên Hiệp Quốc lên án các “ hành động vi phạm nhân quyền phổ biến, liên tục và có hệ thống lâu nay tại Bắc Triều Tiên”.

Ngoài ra, phát ngôn viên Phủ Cao ủy Nhân quyền Liên Hiệp Quốc cũng chỉ trích Thái Lan đã trục xuất không rõ lý do hai công dân Trung Quốc, đã được công nhận quy chế tị nạn, được quyền hưởng chế độ tái định cư ở nước thứ ba.

Phát ngôn viên Phủ Cao ủy tị nạn lấy làm quan ngại rằng “hành động này của Thái Lan chỉ xảy ra vài tháng sau khi nước này bị chỉ trích mạnh mẽ vụ trục xuất 109 người Duy Ngô Nhĩ, một sắc tộc thiểu số theo đạo Hồi tại Trung Quốc”.

Bà Shamdasani nhắc lại là: “Nguyên tắc không trao trả nghiêm cấm việc cưỡng bức hồi hương một người tị nạn đến từ một quốc gia mà ở đó họ có thể phải đối mặt với các hành động đàn áp hay tra tấn. Nguyên tắc này đã được ghi trong điều khoản 3 của Hiệp ước chống Tra tấn hay những hành động Đối xử hoặc Trừng phạt bạo tàn, vô nhân đạo hay gây tổn thương khác, mà Thái Lan vẫn thường hay sử dụng”.

Cuối cùng, bà Shamdasani kêu gọi chính phủ Việt Nam và Trung Quốc làm rõ số phận những người Bắc Triều Tiên nói trên, đồng thời kêu gọi cả hai chính phủ nên hạn chế việc cưỡng bức hồi hương những công dân bỏ trốn khỏi Bắc Triều Tiên.

- VN ‘bắt nhà hoạt động giúp tỵ nạn Bắc Hàn’ — (BBC).

Hàng trăm người đã tới Hàn Quốc từ Việt Nam

Các hãng thông tấn đưa tin một nhà hoạt động Hàn Quốc chuyên giúp người tỵ nạn Bắc Hàn đào tẩu vừa bị bắt hồi tuần trước tại TP. Hồ Chí Minh.

Hãng tin Pháp AFP dẫn nguồn Bộ Ngoại giao Hàn Quốc nói người này bị giới chức Việt Nam bắt vì giúp người Bắc Hàn chạy tới Nam Hàn qua con đường Việt Nam.

Phát ngôn viên của bộ này nói với AFP rằng người đàn ông họ là Yoo, 51 tuổi, bị "nhân viên an ninh" bắt tại một khách sạn ở TP Hồ Chí Minh vào thứ Tư tuần trước 13/6.

Trong khi đó, thông tấn xã Hàn Quốc Yonhap, dẫn lời quan chức sứ quán Hàn Quốc tại Hà Nội, xác nhận ông Yoo bị bắt vì "công việc giúp người tỵ nạn", nhưng không rõ chính xác là công việc gì.

Cho tới nay, chính phủ Việt Nam chưa đưa ra lý do cho vụ bắt ông Yoo vì quá trình điều tra còn tiếp diễn.

Bộ Ngoại giao Hàn Quốc cũng đã yêu cầu được phỏng vấn ông.

Các kênh chính thức của Việt Nam không hề có tin tức gì về vụ bắt giữ này.

Rắc rối ngoại giao

Hàng chục nghìn người Bắc Hàn đã bỏ trốn trong những năm qua vì đói kém và bị trấn áp.Hàn Quốc là đích đến của đa số, tới nay con số người Bắc Hàn đào tẩu xuống miền Nam đã lên tới trên 20.000.

Tuy nhiên để đến được Hàn Quốc, người Bắc Hàn thường phải qua một hay nhiều nước thứ ba khác, như Trung Quốc và các quốc gia Đông Nam Á.

Từ khi Trung Quốc siết chặt quản lý biên giới và trục xuất tất cả người tỵ nạn Bắc Hàn bắt được tại nước này, dòng người tỵ nạn chuyển sang các nước phía Nam, trong đó có Việt Nam, gây khá nhiều rắc rối về ngoại giao.

Năm 2004, khoảng 400 người tỵ nạn Bắc Hàn đã được chuyển từ Việt Nam tới Hàn Quốc trong một sự kiện thu hút nhiều chú ý.

Việt Nam không muốn tạo tiền lệ trở thành điểm trung chuyển của người tỵ nạn Bắc Hàn, và cũng không muốn gây căng thẳng với Bình Nhưỡng.

Thế nhưng Hàn Quốc là nước đầu tư nhiều vào Việt Nam, và Hà Nội cũng muốn giữ quan hệ tốt với Seoul.

Đa phần các cuộc đào tẩu của người Bắc Hàn đều có sự liên quan giúp đỡ của các nhà hoạt động Nam Hàn.

- VN ‘bắt nhà hoạt động giúp tỵ nạn Bắc Hàn’ — (BBC).

-Trung Quốc quyết định viện trợ Bắc Hàn-30.01.12 -– Trung Quốc viện trợ Triều Tiên không điều kiện (NLĐ).- Nga đồng ý xóa 90% nợ thời Liên Xô cho Triều Tiên (TTXVN). --

-, 'Việt Nam cần có trách nhiệm với Bắc Hàn'-10.01.12

-, Người tỵ nạn Bắc Hàn đi Hàn Quốc-20.10.09

-Người Bắc Hàn chờ tị nạn ở HN-25.09.09

-, Người Bắc Hàn xin tị nạn ở Hà Nội-24.09.09

- Câu chuyện tị nạn của một giáo dân Cồn Dầu — (NV).

- Hiểm họa tham nhũng ở Trung Quốc: Nghịch lý song song (NNVN).

-

China News: Một góc đáy xã hội Trung Quốc qua ảnh

Tranh giành quyền lực ở Trung Quốc: Children of Mao's wrath vie for power in China (Reuters 22-6-12)◄--Bắc Kinh bắt đầu kiểm duyệt South China Morning Post? Hong Kong Newspaper Charged With Downplaying Dissident’s Death (Reuters NYT 21-6-12)

Vụ Bạc Hi Lai - Từ Minh: A Tycoon Rises and Falls With a Chinese Leader (WSJ 22-6-12)-Báo Nhật: Vợ Bạc Hy Lai thừa nhận giết doanh nhân Anh

- Cao Ủy Tị Nạn LHQ bổ nhiệm phụ nữ Việt làm đại diện tại Úc — (NV).

Tại sao Trung Quốc sẽ không sụp đổ? Why China Won't Collapse (National Interest 22-6-12) -- Phải nghiến răng mà đọc! (Thằng cha này là giảng viên về Triết học tây phương ở Đại học Thanh Hoa)

E-marketing - Để dạy học: E-Tailer Customization: Convenient or Creepy? (NYT 23-6-12)

-Arts & Letters Daily (25 Jun 2012)

-More than 12 million civilians were expelled from their birthplaces; at least 500,000 died: This is the European atrocity you never heard about... more

June 11, 2012

The European Atrocity You Never Heard About

Hoover Institution Archives

In the largest episode of forced migration in history, millions of German-speaking civilians were sent to Germany from Czechoslovakia (above) and other European countries after World War II by order of the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union.By R.M. Douglas

The screams that rang throughout the darkened cattle car crammed with deportees, as it jolted across the icy Polish countryside five nights before Christmas, were Dr. Loch's only means of locating his patient. The doctor, formerly chief medical officer of a large urban hospital, now found himself clambering over piles of baggage, fellow passengers, and buckets used as toilets, only to find his path blocked by an old woman who ignored his request to move aside. On closer examination, he discovered that she had frozen to death.

Finally he located the source of the screams, a pregnant woman who had gone into premature labor and was hemorrhaging profusely. When he attempted to move her from where she lay into a more comfortable position, he found that "she was frozen to the floor with her own blood." Other than temporarily stanching the bleeding, Loch was unable to do anything to help her, and he never learned whether she had lived or died. When the train made its first stop, after more than four days in transit, 16 frost-covered corpses were pulled from the wagons before the remaining deportees were put back on board to continue their journey. A further 42 passengers would later succumb to the effects of their ordeal, among them Loch's wife.

Hoover Institution Archives

An estimated 500,000 people died in the course of the organized expulsions; survivors were left in Allied-occupied Germany to fend for themselves.

During the Second World War, tragic scenes like those were commonplace, as Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin moved around entire populations like pieces on a chessboard, seeking to reshape the demographic profile of Europe according to their own preferences. What was different about the deportation of Loch and his fellow passengers, however, was that it took place by order of the United States and Britain as well as the Soviet Union, nearly two years after the declaration of peace.

Between 1945 and 1950, Europe witnessed the largest episode of forced migration, and perhaps the single greatest movement of population, in human history. Between 12 million and 14 million German-speaking civilians—the overwhelming majority of whom were women, old people, and children under 16—were forcibly ejected from their places of birth in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, and what are today the western districts of Poland. As The New York Times noted in December 1945, the number of people the Allies proposed to transfer in just a few months was about the same as the total number of all the immigrants admitted to the United States since the beginning of the 20th century. They were deposited among the ruins of Allied-occupied Germany to fend for themselves as best they could. The number who died as a result of starvation, disease, beatings, or outright execution is unknown, but conservative estimates suggest that at least 500,000 people lost their lives in the course of the operation.

Most disturbingly of all, tens of thousands perished as a result of ill treatment while being used as slave labor (or, in the Allies' cynical formulation, "reparations in kind") in a vast network of camps extending across central and southeastern Europe—many of which, like Auschwitz I and Theresienstadt, were former German concentration camps kept in operation for years after the war. As Sir John Colville, formerly Winston Churchill's private secretary, told his colleagues in the British Foreign Office in 1946, it was clear that "concentration camps and all they stand for did not come to an end with the defeat of Germany." Ironically, no more than 100 or so miles away from the camps being put to this new use, the surviving Nazi leaders were being tried by the Allies in the courtroom at Nuremberg on a bill of indictment that listed "deportation and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population" under the heading of "crimes against humanity."

By any measure, the postwar expulsions were a manmade disaster and one of the most significant examples of the mass violation of human rights in recent history. Yet although they occurred within living memory, in time of peace, and in the middle of the world's most densely populated continent, they remain all but unknown outside Germany itself. On the rare occasions that they rate more than a footnote in European-history textbooks, they are commonly depicted as justified retribution for Nazi Germany's wartime atrocities or a painful but necessary expedient to ensure the future peace of Europe. As the historian Richard J. Evans asserted in In Hitler's Shadow(1989) the decision to purge the continent of its German-speaking minorities remains "defensible" in light of the Holocaust and has shown itself to be a successful experiment in "defusing ethnic antagonisms through the mass transfer of populations."

Even at the time, not everyone agreed. George Orwell, an outspoken opponent of the expulsions, pointed out in his essay "Politics and the English Language" that the expression "transfer of population" was one of a number of euphemisms whose purpose was "largely the defense of the indefensible." The philosopher Bertrand Russell acidly inquired: "Are mass deportations crimes when committed by our enemies during war and justifiable measures of social adjustment when carried out by our allies in time of peace?" A still more uncomfortable observation was made by the left-wing publisher Victor Gollancz, who reasoned that "if every German was indeed responsible for what happened at Belsen, then we, as members of a democratic country and not a fascist one with no free press or parliament, were responsible individually as well as collectively" for what was being done to noncombatants in the Allies' name.

That the expulsions would inevitably cause death and hardship on a very large scale had been fully recognized by those who set them in motion. To a considerable extent, they were counting on it. For the expelling countries—especially Czechoslovakia and Poland—the use of terror against their German-speaking populations was intended not simply as revenge for their wartime victimization, but also as a means of triggering a mass stampede across the borders and finally achieving their governments' prewar ambition to create ethnically homogeneous nation-states. (Before 1939, less than two-thirds of Poland's population, and only a slightly larger proportion of Czechoslovakia's, consisted of gentile Poles, Czechs, or Slovaks.)

For the Soviets, who had "compensated" Poland for its territorial losses to the Soviet Union in 1939 by moving its western border more than 100 miles inside German territory, the clearance of the newly "Polish" western lands and the dumping of their millions of displaced inhabitants amid the ruins of the former Reich served Stalin's twin goals of impeding Germany's postwar recovery and eliminating any possibility of a future Polish-German rapprochement. The British viewed the widespread suffering that would inevitably attend the expulsions as a salutary form of re-education of the German population. "Everything that brings home to the Germans the completeness and irrevocability of their defeat," Deputy Prime Minister Clement Richard Attlee wrote in 1943, "is worthwhile in the end." And the Americans, as Laurence Steinhardt, ambassador to Prague, recorded, hoped that by displaying an "understanding" and cooperative attitude toward the expelling countries' desire to be rid of their German populations, the United States could demonstrate its sympathy for those countries' national aspirations and prevent them from drifting into the Communist orbit.

The Allies, then, knowingly embarked on a course that, as the British government was warned in 1944 by its own panel of experts, was "bound to cause immense suffering and dislocation." That the expulsions did not lead to the worst consequences that could be expected from the chaotic cattle drive of millions of impoverished, embittered, and rootless deportees into a war-devastated country that had nowhere to put them was due to three main factors.

The first was the skill with which the postwar German chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, drew the expellees into mainstream politics, defusing the threat of a potentially radical and disruptive bloc. The second was the readiness of most expellees—the occasionally crass or undiplomatic statements of their leaders notwithstanding—to renounce the use or threat of force as a means of redressing their grievances. The third, and by far the most important, was the 30-year-long "economic miracle" that made possible the housing, feeding, and employment of the largest homeless population with which any industrial country has ever had to contend. (In East Germany, on the other hand, the fact that the standard of living for the indigenous population was already so low meant that the economic gap between it and the four million arriving expellees was more easily bridged.)

The downside of "economic miracles," though, is that, as their name suggests, they can't be relied upon to come along where and when they are most needed. By extraordinary good fortune, the Allies avoided reaping the harvest of their own recklessness. Nonetheless, the expulsions have cast a long and baleful shadow over central and southeastern Europe, even to the present day. Their disruptive demographic, economic, and even—as Eagle Glassheim has pointed out—environmental consequences continue to be felt more than 60 years later. The overnight transformation of some of the most heterogeneous regions of the European continent into virtual ethnic monoliths changed the trajectory of domestic politics in the expelling countries in significant and unpredicted ways. Culturally, the effort to eradicate every trace of hundreds of years of German presence and to write it out of national and local histories produced among the new Polish and Czech settler communities in the cleared areas what Gregor Thum has described as a state of "amputated memory." As Thum shows in his groundbreaking study of postwar Wroclaw—until 1945 and the removal of its entire population, the German city of Breslau—the challenge of confronting their hometown's difficult past is one that post-Communist Wroclawites have only recently taken up. In most other parts of Central Europe, it has hardly even begun.

Still less so in the English-speaking world. It is important to note that the expulsions are in no way to be compared to the genocidal Nazi campaign that preceded them. But neither can the supreme atrocity of our time become a yardstick by which gross abuses of human rights are allowed to go unrecognized for what they are. Contradicting Allied rhetoric that asserted that World War II had been fought above all to uphold the dignity and worth of all people, the Germans included, thousands of Western officials, servicemen, and technocrats took a full part in carrying out a program that, when perpetrated by their wartime enemies, they did not hesitate to denounce as contrary to all principles of humanity.

The degree of cognitive dissonance to which this led was exemplified by the career of Colonel John Fye, chief U.S. liaison officer for expulsion affairs to the Czechoslovak government. The operation he had helped carry out, he acknowledged, drew in "innocent people who had never raised so much as a word of protest against the Czechoslovak people." To accomplish it, women and children had been thrown into detention facilities, "many of which were little better than the ex-German concentration camps." Yet these stirrings of unease did not prevent Fye from accepting a decoration from the Prague government for what the official citation candidly described as his valuable services "in expelling Germans from Czechoslovakia."

Today we have come not much further than Fye did in acknowledging the pivotal role played by the Allies in conceiving and executing an operation that exceeded in both scale and lethality the violent breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. It is unnecessary to attribute this to any "taboo" or "conspiracy of silence." Rather, what is denied is not the fact of the expulsions themselves, but their significance.

Many European commentators have maintained that to draw attention to them runs the risk of diminishing the horror that ought properly to be reserved for the Holocaust and other Nazi atrocities, or giving rise to a self-pitying "victim" mentality among today's generation of Germans, for whom the war is an increasingly distant memory. Czechs, Poles, and citizens of other expelling states fear the legal ramifications of a re-examination of the means by which millions of erstwhile citizens of those countries were deprived of their nationality, liberty, and property. To this day, the postwar decrees expropriating and denationalizing Germans remain on the statute book of the Czech Republic, and their legality has recently been reaffirmed by the Czech constitutional court.

Some notable exceptions aside, like T. David Curp, Matthew Frank, and David Gerlach, English-speaking historians—out of either understandable sympathy for Germany's victims or reluctance to complicate the narrative of what is still justifiably considered a "good war"—have also not been overeager to delve into the history of a messy, complex, morally ambiguous, and politically sensitive episode, in which few if any of those involved appear in a creditable light.

By no means are all of these concerns unworthy ones. But neither are they valid reasons for failing to engage seriously with an episode of such obvious importance, and to integrate it within the broader narrative of modern European history. For historians to write—and, still worse, to teach—as though the expulsions had never taken place or, having occurred, are of no particular significance to the societies affected by them, is both intellectually and pedagogically unsustainable.

The fact that population transfers are currently making a comeback on the scholarly and policy agenda also suggests that we should scrutinize with particular care the most extensive experiment made with them to date. Despite the gruesome history, enthusiasts continue to chase the mirage of "humane" mass deportations as a means of resolving intractable ethnic problems. Andrew Bell-Fialkoff, in a much-cited study, has advocated population transfers as a valuable tool so long as they are "conducted in a humane, well-organized manner, like the transfer of Germans from Czechoslovakia by the Allies in 1945-47." John Mearsheimer, Chaim Kaufmann, Michael Mann and others have done likewise.

Few wars today, whether within or between states, do not feature an attempt by one or both sides to create facts on the ground by forcibly displacing minority populations perceived as alien to the national community. And although the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court has attempted to restrain this tendency by prohibiting mass deportations, Elazar Barkan maintains that such proscriptions are far from absolute, and that "today there is no single code of international law that explicitly outlaws population transfers either in terms of group or individual rights protections."

The expulsion of the ethnic Germans is thus of contemporary as well as historical relevance. At present, though, the study of many vital elements of this topic is still in its earliest stages. Innumerable questions—about the archipelago of camps and detention centers, the precise number and location of which are still undetermined; the sexual victimization of female expellees, which was on a scale to rival the mass rapes perpetrated by Red Army soldiers in occupied Germany; the full part played by the Soviet and U.S. governments in planning and executing the expulsions—remain to be fully answered. At a moment when the surviving expellees are passing away and many, though far from all, of the relevant archives have been opened, the time has come for this painful but pivotal chapter in Europe's recent history to receive at last the scholarly attention it deserves.

R.M. Douglas is an associate professor of history at Colgate University. This essay is adapted from his new book, published by Yale University Press, Orderly and Humane: The Expulsion of the Germans After the Second World War.